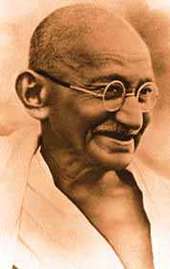

Mohandas K. Gandhi studied law in England, then spent 20 years defending the rights of immigrants in South Africa. In 1914 he returned to India and became the leader of the Indian National Congress. Gandhi urged non-violence and civil disobedience as a means to gain independence from Great Britain, with public acts of defiance that landed him in jail several times. In 1947 he participated in the postwar negotiations that led to Indian independence. He was shot to death by a Hindu fanatic in 1948

Mohandas Gandhi was born on October 2,1869, at Porbandar, on the western coast of India. His grandfather Uttamchand Gandhi and father Karamchand Gandhi occupied the high office of the diwan (Chief Minister) of Porbandar. To be Diwan of one of the princely states was no sinecure. Porbandar was one of some three hundred native states in western India which were ruled by princes whom the accident of birth and the support of the British kept on the throne. To steer ones course safely between wayward Indian princes, the overbearing British Political Agent of the suzerain power and the long-suffering subjects required a high degree of patience, diplomatic skill and commonsense. Both Uttamchand and Karamchand were good administrators. But they were also upright and honourable men. Loyal to their masters, they did not flinch from offering unpalatable advice. They paid the price for the courage of their convictions. Uttamchand Gandhi had his house besieged and shelled by the rulers troops and had to flee the State; his son Karamchand also preferred to leave Porbandar, rather than compromise with his principles

Karamchand Gandhi was, in the words of his son, "a lover of his clan, truthful, brave, generous." The strongest formative influence on young Mohandas, however, was that of his mother Putlibai. She was a capable woman who made herself felt in court circles through her friendship with the ladies of the palace, but her chief interest was in the home. When there was sickness in the family, she wore herself out in days and nights of nursing. She had little of the weaknesses, common to women of her age and class, for finery or jewellery. Her life was an endless chain of fasts and vows through which her frail frame seemed to be borne only by the strength of her faith. The children clung to her as she divided her day between the home and the temple. Her fasts and vows puzzled and fascinated them. She was not versed in the scriptures; indeed except for a smattering of Gujarati, she was practically unlettered. But her abounding love, her endless austerities and her iron will, left a permanent impression upon Mohandas, her youngest son. The image of woman he imbibed from his mother was one of love and sacrifice. Something of her maternal love he came to possess himself, and as he grew, it flowed out in an ever-increasing measure, bursting the bonds of family and community, until it embraced the whole of humanity. To his mother, he owed not only a passion for nursing which later made him wash lepers sores in his ashram, but also an inspiration for his techniques of appealing to the heart through self-suffering a technique which wives and mothers have practised from time immemorial

Young Mohandas school career was undistinguished. He did not shine in the classroom or in the playground. Quiet, shy and retiring, he was tongue-tied in company. He did not mind being rated as a mediocre student, but he was exceedingly jealous of his reputation. He was proud of the fact that he had never told a lie to his teachers or classmates; the slightest aspersion on his character drew his tears. Like most growing children he passed through a rebellious phase, but contrary to the impression fostered by his autobiography, Gandhis adolescence was no stormier than that of many of his contemporaries. Adventures into the forbidden land of meat-eating and smoking and petty pilfering were, and are not uncommon among boys of his age. What was extraordinary was the way his adventures ended. In every case when he had gone astray, he posed for himself a problem for which he sought a solution by framing a proposition in moral algebra. Never again was his promise to himself after each escapade. And he kept the promise

Reporter: "What do you think about western civilization?" Gandhi: "I think it would be a good idea."

..

..

..

..

..