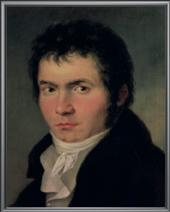

I was born in Bonn, Germany, in 1770. Although there is no record of my birth, I was baptized on December 17, and my friends, family and I celebrate my birthday on December 16.

My father, Johann, was a tenor in the service of the Electoral court of Bonn. He would sometimes come home from the tavern late at night (or early in the morning, depending on how you look at it), get me up out of bed, and force me to play the clavier for his friends.

My mother, Maria Magdalena, was a very sweet, caring woman, and my best friend. Once, when the Rhine flooded our home, she escorted my younger brothers, Johann and Karl, and me to safety across the rooftops of the neighbors' houses.

When I was young, my father wanted to turn me into another Mozart, even falsifying my birth records to say that I was two years younger than I actually was. I believed this until I was in my early twenties, about the same time I realized that I was loosing my very most precious sense, hearing.

When I was 18 I traveled to Vienna for the first time in the hope of studying with the great Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. However, soon after arriving, I recived a letter from my father stating that my mother was gravely ill. I rushed back to Bonn immediately. My beloved mother passed away from consumption on July 17, 1787. After that, my father lost his job and I became the sole provider for him and my brothers.

I came back to Vienna when I was 22, but unforturnately, Mozart had died by the time I returned. I took lessons briefly with Haydn, but we had a personality clash, so then I took lessons from Albrechtsberger and Salieri.

My first symphony debuted in 1800. The audience at the time, who was used to the works of Mozart and Haydn, found my composition to be strange and daring. Little did they know that I would later take the symphony to heights never before imagined by my great predecessors.

In 1809, I was tempted to leave Vienna, but I was pursuaded to stay by the local nobility, who offered me a salary of 4,000 florins a year, as long as I stay in Vienna. This enabled me a freedom not enjoyed by previous masters, as musicians at the time were considered servants, their works subject to approval by the nobility. I was the first great composer who was able to write whatever I wanted, whenever I wanted.

In 1802 I moved to Heiliginstadt for a short time, where I wrote the now famous "Heiliginstadt Testament," a letter to my brothers in which I first admit that I am losing my hearing. This is one of several documents which I wrote but then hid away, showing it to no one during my lifetime.

A friend arranged for me to meet the great German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in 1812. Although we admired each other, Goethe is known to have said that I was "completely untamed." I always regretted not having been better understood by this great artist.

In 1815 my youngest brother, Karl, passed away, leaving behind a son, Karl, who was 9 at the time. Karl's mother, Johanna, was a completely immoral woman, and since my brother's will had stated that I be Karl's sole guardian, I saw no reason for the wretched Johanna to have anything to do with my nephew's life. We battled in the courts for many years over Karl's fate, which perhaps was the "ispiration" (if you can call it that) for that terrible movie about me which premiered in 1994. (Honestly, does Gary Oldman resemble me even in the slightest? I think not.)

As my deafness increased, my creative productivity dwindled, and performed even less often. It was during this time, however, that I composed my 9th symphony, which many consider one of my greatest accomplishments.

The symphony debuted in 1824. When the audience applauded (I can't remember if it was at the end of the scherzo or the end of the 4th movement...), I was still conducting, for I was several measures off... one of the performers came up and gently turned me around so that I could see the thunderous applause from the audience.

In 1826, my nephew and I went to stay with my brother Johann. One night, Johann and I had a terrible fight, and Karl and I left immediately for Vienna in an open carriage, despite the horrible weather.

I caught cold that night, which soon turned into pneumonia from which I never recovered.

On March 26, 1827, as I lie on my deathbed, there was a terrible thunderstorm. At one point, there was a great flash of lightening, whereupon I raised my clentched fist towards the heavens... and I passed into the spirit world.

Layout by CoolChaser