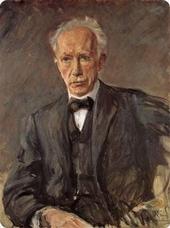

Richard Strauss

from http://www.evermore.com (with a few additions) Born Munich, 11 June, 1864; died September 8, 1949, Garmisch-PartenkirchenRichard Strauss - not to be confused with a member of the Strauß "Waltz Dynasty", whose name spells with the diacritical "ß" - was a German composer of the late Romantic era and early modern era, particularly famous for his tone poems and operas. He was also one of the premier conductors of his time.

His artistic education was strictly conservative, his well-mannered, well-heeled appearance that of a stolid investment banker, yet his music shocked the world. Richard Strauss stirred controversy with iconoclastic symphonic works that inspired avid debate throughout contemporary music circles, as well as with erotic operas that literally incited crowds to riot.

Strauss was born in Munich in June, 1864. His father, Franz, was a fiery artist himself and the most highly ranked horn player in Germany, hand-picked by Richard Wagner for several of the Maestro's world premiere orchestras. Notably, the well publicized volcanic relationship of Franz Strauss, impresario-conductor Hans von Bülow, and Wagner was characterized by regular heated exchanges and feuds. Franz made no secret of his dislike for Wagner's horn composition and von Bulow's authoritarianism; an amazingly independent attitude for any freelance musician toward two artistic heavyweights. Wagner and Bülow allowed Franz his disdainful bent because they simply could not replace him. Meanwhile, certain that no one since Mendelssohn had written anything worthwhile, Franz preached from an anti-Wagnerian pulpit to his son, Richard, an approach which had little restraining effect, however, on the young man's later style of operatic composition.

Richard received a thoroughly proper music education based securely around his father's rock-solid prejudices. Then, true to the program which had been prescribed for him, the youthful Strauss began his career, predictably enough, with the composition and performance of several innocuously conservative symphonic pieces and a few seasons of piano recitals in Berlin. His Suite for Winds in B Flat won the approval of the famous conductor, von Bülow, and, on the spur of the moment, Strauss found himself standing at the podium before the Munich Symphony Orchestra, about to conduct the debut of his own score.

The quivering Strauss had never held a baton before and in later years realized he spent the entire performance in an uncomprehending shock. Nonetheless, Strauss soon became von Bülow's assistant and ultimately as noted for his work as a conductor as he was as a composer. In 1885, upon von Bülow's resignation, Strauss took charge of the Munich orchestra. Otherwise, the composer continued, for the moment, on a mundanely marketable creative track. At least, until he met Alexander Ritter, an accomplished violinist and husband to Richard Wagner's niece, Franziska. Ritter and Strauss initiated their friendship around tireless discussions of Wagner's influence on concepts of harmonic structure, orchestration, and the overall artistic vocabulary of the later nineteenth century.

Strauss transferred these revelations to his compositional palette and, as one modern musicologist put it, "All hell broke loose." In 1889, the performance of the composer's first tone poem, Don Juan , left the audience standing: half of them cheering -- half of them booing. Said Strauss, "I now comfort myself with the knowledge that I am on the road I want to take, fully conscious that there never has been an artist not considered crazy by thousands of his fellow men."

Having found a niche for himself, Strauss continued in the same musical vein with more and more sensational efforts at the symphonic poem: Till Eulenspiegel , Don Quixote , Also sprach Zarathustra, Ein Heldenleben , Sinfonia Domestica, and Eine Alpensinfonia among them. In the creative tradition of Wagner, Strauss' music subscribed to its own symbolism and attachment to literary roots, as well as to the Wagnerian technique utilizing an orchestra of gargantuan proportions to give full benefit to music of enormous melodic and harmonic complexity, Strauss added the challenge to audiences of a uniquely unsettlingly dissonant quality. And, although evocative of the leitmotiv -- at times suggestive of the sounds of thunder storms, bleating animals, human conflicts - Strauss' work, like much of Wagner's, also stood on its own as absolute music, not necessarily to be viewed as simply symbolic or programmatic.

A supercilious Saint-Saens commented, "The desire to push works of art beyond the realm of art means simply to drive them into the realm of folly. Richard Strauss is in the process of showing us the road." Yet from Claude Debussy came praise for the "tremendous versatility of the orchestration, the frenzied energy which carries the listener with him for as long as he chooses...One must admit that the man who composed such work at so continually high a pressure is very nearly a genius."

[Footnote: As far-fetched as it may seem, Debussy's "Pelléas et Mélisande" (1902) appears to have influenced Strauss' "Frau ohne Schatten", as demonstrated by the bars which open the excerpt of the "Symphonic Fantasy" on the opera (1946) featured on this page. Likewise, a comparison between Hoffmannsthals libretto and Maurice Maeterlincks previous symbolistic masterpiece "Pelléas" (1892) - which inspired music from the likes of Schönberg - may not entirely be without merit. (ASL) ]

Was it the dawning of the avant garde or the death throes of Romanticism? The birth of modernism or the elevation of mediocrity? Subsequent to each and every premiere, the battle raged. Whatever else it was, it was news. And the most compelling was yet to come. Strauss set his sights on operatic composition. A first effort, Guntram , clearly mimicked Wagner and ran for one performance at Weimar. A second bid, Feuersnot , also encountered damning criticism.

In 1905, with Salome , Strauss found operatic immortality as the composer of the most scandalously sensational stage production of his era. The decadence and obsessed eroticism astonished fin de siecle audiences. A Metropolitan Opera production opened one evening, closed the next, in reaction to public outcry. At the world premiere in Dresden, the first Salome, Marie Wittich, protested the staging of the infamous "Dance of the Seven Veils." "I won't do it," she exclaimed, "I'm a decent woman." And, for some years after it was traditional for a ballerina to perform the dance role as a double for the principal soprano.

While the pulpit and public registered their varied angry appraisals even the Kaiser of Germany, Wilhelm II, predicted "damage" to Richard Strauss' career and reputation. Ever the businessman, Strauss noted that over the next several years, as new productions of Salome continued to open before curious patrons around the globe, the "damage" provided funds to build a substantial villa at Garmisch.

His next opera, Elektra, not only resurrected the atmosphere of protest and scandal initiated by Salome , but created an additional artistic war zone. Strauss' requirement for voices of Wagnerian strength singing with a violent dissonance drew the wrath of the music community. This signaled, experts theorized, not only the end of operatic tradition, but the demise of the human voice as an artistic instrument.

Then, as suddenly as it had emerged, Strauss' decade of creative iconoclasm ended. Beginning with Der Rosenkavalier , which Strauss proposed as his first Mozartian effort, the convulsively violent and sensational bent was over. Ariadne auf Naxos, Ariadne , Die Frau ohne Schatten , Die agyptische Helena, Arabella, followed each other with happy regularity between 1911 and 1933. Each was received with polite applause by appreciative audiences and critics, not a little surprised at the one-hundred-eighty-degree shift in Strauss' approach.

When the Third Reich came to power, authorities found it essential to place Strauss in the "Reichsmusikkammer," in acknowledgment of his rank as the most important composer in the nation. Completely apolitical, Strauss continued composing to his own purposes, unwittingly offending authorities on regular occasions. His uneasy and apparently useless relationship with the Nazi regime continued for several years. His family eventually lived under house arrest until they managed to emigrate to Switzerland to wait out the last years of the war. Yet, once more, Strauss attracted strong criticism from some who felt he should have utilized his position as "court composer" to protest the Hitler dictatorship.

Wherever Strauss' artistic aberrations, astronomical earnings and political uncertainties failed to provide sufficient copy for the press, tales of his life with wife Pauline filled the gaps. He had met Pauline de Ahna, when she sang under his direction at the opera house in Munich. Reportedly, they argued violently during rehearsals. On one such occasion, Strauss met with Pauline in her dressing room to smooth over the quarrel, and emerged an engaged man. Their relationship was legendary as that of domineering wife and henpecked husband. The artistically rebellious Strauss seemed to thrive on his wife's "law and order" approach to marriage. His slack habits of composition were soon set to rights by Pauline who, noticing him wandering through the house without apparent purpose would shout with military authority, "Richard, go compose!" And Strauss would diffidently oblige.

How extraordinarily contradictory that, by the time of his death in 1949, Richard Strauss had achieved the strange distinction of living a quiet, remarkably scandal-free life, without the slightest indication of eccentricity; a practical businesslike artist, a conductor with a nearly emotionless technique, a happily married obedient husband, who had ignited a string of artistic Roman candles which will keep audiences gasping and applauding well into the next century.