(From: http://w3.rz-berlin.mpg.de/cmp/wagner.html)

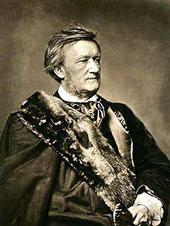

Richard Wagner

Born Leipzig, 22 May 1813; died Venice, 13 February 1883 Richard Wagner was the son either of the police actuary Friedrich Wagner, who died soon after his birth, or of his mother's friend the painter, actor and poet Ludwig Geyer, whom she married in August 1814. He went to school in Dresden and then Leipzig; at 15 he wrote a play, at 16 his first compositions. In 1831 he went to Leipzig University, also studying music with the Thomaskantor, C.T. Weinlig; a symphony was written and successfully performed in 1832. In 1833 he became chorus master at the Würzburg theatre and wrote the text and music of his first opera, Die Feen; this remained unheard, but his next, Das Liebesverbot, written in 1833, was staged in 1836. By then he had made his début as an opera conductor with a small company which however went bankrupt soon after performing his opera. He married the singer Minna Planer in 1836 and went with her to Königsberg where he became musical director at the theatre, but he soon left and took a similar post in Riga where he began his next opera, Rienzi, and did much conducting, especially of Beethoven.In 1839 they slipped away from creditors in Riga, by ship to London and then to Paris, where he was befriended by Meyerbeer and did hack-work for publishers and theatres. He also worked on the text and music of an opera on the 'Flying Dutchman' legend; but in 1842 Rienzi, a large-scale opera with a political theme set in imperial Rome, was accepted for Dresden and Wagner went there for its highly successful premiere. Its theme reflects something of Wagner's own politics (he was involved in the semi-revolutionary, intellectual 'Young Germany' movement). Die fliegende Holländer ('The Flying Dutchman'), given the next year, was less well received, though a much tauter musical drama, beginning to move away from the 'number opera' tradition and strong in its evocation of atmosphere, especially the supernatural and the raging seas (inspired by the stormy trip from Riga). Wagner was now appointed joint Kapellmeister at the Dresden court.

The theme of redemption through a woman's love, in the Dutchman, recurs in Wagner's operas (and perhaps his life). In 1845 Tannhäuser was completed and performed and Lohengrin begun. In both Wagner moves towards a more continuous texture with semi-melodic narrative and a supporting orchestral fabric helping convey its sense. In 1848 he was caught up in the revolutionary fervour and the next year fled to Weimar (where Liszt helped him) and then Switzerland (there was also a spell in France); politically suspect, he was unable to enter Germany for 11 years. In Zürich, he wrote in 1850-51 his ferociously anti-semitic Jewishness in Music (some of it an attack on Meyerbeer) and his basic statement on musical theatre, Opera and Drama; he also began sketching the text and music of a series of operas on the Nordic and Germanic sagas. By 1853 the text for this four-night cycle (to be The Nibelung's Ring) was written, printed and read to friends - who included a generous patron, Otto Wesendonck, and his wife Mathilde, who loved him, wrote poems that he set, and inspired Tristan und Isolde - conceived in 1854 and completed five years later, by which time more than half of The Ring was written. In 1855 he conducted in London; tension with Minna led to his going to Paris in 1858-9. 1860 saw them both in Paris, where the next year he revived Tannhäuser in revised form for French taste. but it was literally shouted down, partly for political reasons. In 1862 he was allowed freely into Germany; that year he and the ill and childless Minna parted (she died in 1866). In 1863 he gave concerts in Vienna, Russia etc; the next year King Ludwig II invited him to settle in Bavaria, near Munich, discharging his debts and providing him with money.

Wagner did not stay long in Bavaria, because of opposition at Ludwig's court, especially when it was known that he was having an affair with Cosima, the wife of the conductor Hans von Bülow (she was Liszt's daughter); Bülow (who condoned it) directed the Tristan premiere in 1865. Here Wagner, in depicting every shade of sexual love, developed a style richer and more chromatic than anyone had previously attempted, using dissonance and its urge for resolution in a continuing pattem to build up tension and a sense of profound yearning; Act 2 is virtually a continuous love duet, touching every emotion from the tenderest to the most passionately erotic. Before returning to the Ring, Wagner wrote, during the mid-1860s, The Mastersingers of Nuremberg: this is in a quite different vein, a comedy set in 16th-century Nuremberg, in which a noble poet-musician wins, through his victory in a music contest - a victory over pedants who stick to the foolish old rules - the hand of his beloved, fame and riches. (The analogy with Wagner's view of himself is obvious.) The music is less chromatic than that of Tristan, warm and good-humoured, often contrapuntal; unlike the mythological figures of his other operas the characters here have real humanity.

The opera was given, under Bülow, in 1868; Wagner had been living at Tribschen, near Lucerne, since 1866, and that year Cosima formally joined him, they had two children when in 1870 they married. The first two Ring operas, Das Rheingold and Die Walküre, were given in Munich, on Ludwig's insistence, in 1869 and 1870; Wagner however was anxious to have a special festival opera house for the complete cycle and spent much energy trying to raise money for it. Eventually, when he had almost despaired, Ludwig came to the rescue and in 1874 - the year the fourth opera, Götterdämmerung, was finished - provided the necessary support. The house was built at Bayreuth, designed by Wagner as the home for his concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk ('total art work'- an alliance of music, poetry, the visual arts, dance etc). The first festival, an artistic triumph but a financial disaster - was held there in 1876, when the complete Ring was given. The Ring is about 18 hours' music, held together by an immensely detailed network of themes, or leitmotifs, each of which has some allusive meaning: a character, a concept, an object etc. They change and develop as the ideas within the opera develop. They are heard in the orchestra, not merely as 'labels' but carrying the action, sometimes informing the listener of connections of ideas or the thoughts of those on the stage. There are no 'numbers' in the Ring; the musical texture is made up of narrative and dialogue, in which the orchestra partakes. The work is not merely a story about gods, humans and dwarfs but embodies reflections on every aspect of the human condition. It has been interpreted as socialist, fascist, Jungian, prophetic, as a parable about industrial society, and much more.

In 1877 Wagner conducted in London, hoping to recoup Bayreuth losses; later in the year he began a new opera, Parsifal. He continued his musical and polemic writings, concentrating on 'racial purity'. He spent most of 1880 in Italy. Parsifal, a sacred festival drama, again treating redemption but through the acts of communion and renunciation on the stage, was given at the Bayreuth Festival in 1882. He went to Venice for the winter, and died there in February of the heart trouble that had been with him for some years. His body was retumed by gondola and train for burial at Bayreuth. Wagner did more than any other composer to change music, and indeed to change art and thinking about it. His life and his music arouse passions like no other composer's. His works are hated as much as they are worshipped; but no-one denies their greatness.

========================================

Project completed

Ok I'm done guys========================================