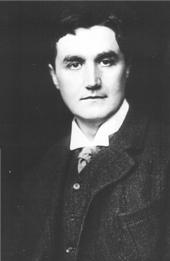

I was born in Down Ampney, Gloucestershire, where my father, the Rev. Arthur Vaughan Williams, was vicar. Following my father's death in 1875, my mother, Margaret Susan Wedgwood, took me to live with her family at Leith Hill Place in the North Downs. I was therefore born into the privileged intellectual upper middle class, but never took it for granted and worked tirelessly all my life for the democratic and egalitarian ideals I believed in. As a student, I studied piano which I never could play, and the violin, which was my musical salvation. I attended the Royal College of Music (RCM) under Charles Villiers Stanford. I read history and music at Trinity College, Cambridge where my friends and contemporaries included the philosophers G. E. Moore and Bertrand Russell. I then returned to the RCM and studied composition with Hubert Parry, who became a close friend. One of my fellow pupils at the RCM was Leopold Stokowski and during 1896 we both studied organ under Sir Walter Parratt.

My composing developed slowly and it was not until age 30 that the song "Linden Lea" became my first publication. I had further lessons with Max Bruch in Berlin in 1897 and later a big step forward in my orchestral style occurred when I studied in Paris with Maurice Ravel. In 1904, I discovered English folk songs, which were fast becoming extinct owing to the increase of literacy and printed music in rural areas. I travelled the countryside, transcribing and preserving many myself. Later I incorporated some songs and melodies into my own music, being fascinated by the beauty of the music and its anonymous history in the working lives of ordinary people. In 1905, I conducted the first concert of the newly founded Leith Hill Music Festival at Dorking and thereafter held that conductorship until 1953. In 1910, I had my first big public successes conducting the premieres of the Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis and A Sea Symphony (Symphony No. 1), and a greater success with A London Symphony (Symphony No. 2) in 1914.

Being 40, I could have avoided war service, but I chose to enlist as a private in the Royal Army Medical Corps and had a grueling time as a stretcher bearer before being commissioned in the Royal Garrison Artillery. On one occasion I was too ill to stand, but I continued to direct my battery while lying on the ground. Prolonged exposure to gunfire began a process of loss of hearing which was eventually to cause deafness in old age.

After the war, I adopted a mystical style in the Pastoral Symphony (Symphony No. 3), which draws on my experiences as an ambulance volunteer in that war. From 1924 a new phase in my music began, characterised by lively cross-rhythms and clashing harmonies. Key works from this period are Toccata Marziale, the ballet Old King Cole, the Piano Concerto, the oratorio Sancta Civitas (my favourite of my choral works) and the ballet Job (described as "A Masque for Dancing") which is drawn not from the Bible but from William Blake's Illustrations to the Book of Job. This period in my music culminated in the Symphony No. 4 in F minor, first played by the BBC Symphony Orchestra in 1935. This symphony contrasts dramatically with the frequent "pastoral" orchestral works I composed; indeed, its almost unrelieved tension, drama, and dissonance has startled listeners since it was premiered. I acknowledge that the fourth symphony was different, I don't know if I like it, but it's what I mean.

My music now entered a mature lyrical phase, as in the Five Tudor Portraits; the "morality" The Pilgrim's Progress; and the Symphony No. 5 in D, which I conducted at the Proms in 1943. As I was now 70, many people considered it a swan song, but I renewed myself again and entered yet another period of exploratory harmony and instrumentation. The very successful Symphony No. 6 of 1946 received a hundred performances in the first year. It surprised both admirers and critics, many of whom suggested that this symphony (especially its last movement) was a grim vision of the aftermath of an atomic war; I refuse to recognise any program behind this work.

By 1958, I had completed three more symphonies. The seventh, Sinfonia Antartica, which was based on the 1948 film score for Scott of the Antarctic, exhibits my renewed interest in instrumentation and sonority. The "Little Eighth Symphony", first performed in 1956, was followed by the much weightier Symphony No. 9 in E minor of 1956-57. This last symphony was initially given a luke-warm reception after its first performance in May 1958. But this dark and enigmatic work is now considered by many to be a fitting conclusion to my sequence of symphonic works.

***

Ralph Vaughan Williams died in 1958 and is buried in Westminster Abbey.

Vaughan Williams is a central figure in British music because of his long career as teacher, lecturer and friend to so many younger composers and conductors. His writings on music remain thought-provoking, particularly his oft-repeated call for everyone to make their own music, however simple, as long as it is truly their own.

Background from flickr user