Fela Ransome Kuti was born on October 15, 1938 and raised by a colonial Christian family of means in the town of Abeokuta, Nigeria. "My father was very strict," he told journalist Roger Steffens in 1986. "I thought he was wicked. He kicked my ass so many times. It was tough in school under our father. That's how he understood life should be, cause he read the Bible: 'Spare the rod and spoil the child.' My mother, she was wicked too. She kicked my ass so much man -- systematic ass kicking. [But] on the whole, they were beautiful parents, they taught me heavy things. They made me see life in perspective. I think if they had not brought me up with these experiences, I do not think I would have been what I am today. So the upbringing was not negative."

Fela left Nigeria and studied music at Trinity College in London from 1958 to 1962. In 1960, Nigeria gained its independence from England in no small part due to the activism of people like his mother, Funmilayo -- a central figure in his Fela's life. Fela married his first wife, Remi, in London in 1961. While Fela studied classical music at Trinity, outside school he studied and played jazz. The first recordings of his band Koola Lobitos are rumored to date from this period. His first verifiable recording was "Aigna" as Fela Ransome Kuti and His Highlife Rakers from around 1961. He also recorded several titles under the name Highlife Jazz Band in the mid to late 60s, and there was a full Koola Lobitos album released by EMI in Nigeria in 1969.

Fela's journey to Los Angeles in 1969 was the most formative experience of his life. In L.A., he met a young Africentric woman named Sandra Smith, who exposed him to the consciousness then sweeping Black America. She gave Fela a copy of Alex Haley's Autobiography of Malcolm X and unknowingly sent him on his way.

"It was incredible how my head was turned," he told the New York Times in 1987. "Everything fell into place. For the first time, I saw the essence of blackism. It's crazy; in the States people think the black power movement drew inspiration from Africa. All these Americans come over here looking for awareness, they don't realize they're the ones who've got it over there. We were even ashamed to go around in national dress until we saw pictures of blacks wearing dashikis on 125th street."

"I wasn't aware I was sending him," says a proudly reflective Sandra (Smith) Isadore. "I was being myself and so happy that I had met an urban African. I was trying to get to my roots in 1969. In my own mind, they (Africans) didn't have a struggle. It came to me as a surprise when I was in Nigeria [in 76] and Fela gave me this credit, cause I had not given the credit to myself."

In L.A., H.B. Barnham recorded the high-life jazz sound of Fela Ransome Kuti and the newly renamed 'Nigeria 70.' Those recordings, recently released by Stern's Africa on CD, are the earliest document of Fela's work currently in print. In 1970, EMI financed a session in London at Abbey Road studio, which became Fela's London Scene. In London, Fela was befriended by percussionist Ginger Baker. Fela appeared on Baker's Stratavarious album and played live shows with the former Cream drummer, one of which was released as Live With Ginger Baker. Later, Baker would produce Fela's classic, He Miss Road. By 1971, Fela's musical career was focused and directed, and it exploded in terms of quantity and quality of output. It was the beginning of his own style of music -- Afrobeat.

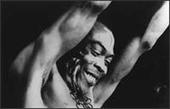

Over the next six years, Fela Ransome Kuti and the Africa 70 would record some twenty albums that are the bedrock of his musical legacy. Classic titles such as Shakara, Afrodisiac,Open & Close,Why Black Men They Suffer, Gentleman, Algabon Close, Expensive Shit, Upside Down, and Confusion established a standard of intricacy and musical ferocity seldom equaled. While Fela himself was not a sensational horn or keyboard player, his compositional skill and ability to assemble and direct crack musicians was the essence of his art. While the whole of the Africa 70 band exuded talent, the trumpet playing of Tunde Williams and the drumming of TONY ALLEN in particular exemplified the best musicianship in Africa.

Dennis Bovell echoes the thought. "I would say he was Africa's number one. He was a great composer, and that's more than a musician. The composers compose shit and any musician can play it. I think he was a great composer, full stop."

In 1974, after the first government attack on Kalakuta Republic (as he was calling his self contained commune in his mother's converted house in the Surulere section of Lagos), Fela's resolve and militancy were reinforced, and it was directly reflected in his music. "I refuse to live my life in fear," he later said. "I don't think about it. If somebody wants to do harm for you, it's better for you not to know. So I don't think about it. I can say I don't care. I'm ready for anything." He changed his name to Anikulapo-Kuti in 1976 to shed his colonial name and emphasize that he was 'one who holds death in his pouch.'

Fela needed death in his pouch to survive the second attack on Kalakuta. Several significant events led to the fateful day. In addition to the increasingly anti-authoritarian tone of his music, Fela purchased a printing press and was distributing an anti-government newsletter in late 1976. He also publicly boycotted FESTAC 77, the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, and in so doing blatantly criticized the dictatorship for their corrupt dealings with foreign multi-national corporations (Shell, I.T.T., etc.).

On February 18th, 1977, the Nigerian government tried to break Fela for good. 1,000 soldiers attacked Kalakuta in an infamous and brutal display of barbarism that left Fela severely beaten, with broken legs. His followers were brutalized and raped. His mother was thrown from a second story balcony, hastening her death. For Fela, it was truly time for musical war. The event ignited retaliation in the form of Sorry Tears and Blood, No Agreement, Zombie, Vagabonds In Power (VIP) and Coffin For Head of State. Fela would mark the anniversiary of the attack in 1978 with a traditional marriage to 27 of his female followers.

Fela's recording career changed with his spiritual outlook in 1981, when he had a vision in a trance. "[Before 1981] I was spiritually aware, but subconsciously spiritually aware," he told Roger Steffens. "It was a trance -- very spiritual and real. It was like a film. I saw this whole [world] was going to change into what people call the Age of Aquarius. The age of goodness where music was going to be the final expression of the human race and musicians were going to be very important in the development of the human society and that musicians would be presidents of different countries and artists would be dictators of society. The mind would be freer, less complicated institutions, less complicated technologies. It was in that trance that I saw the aspect of the Egyptian civilization. The whole human race were in Egypt under the spiritual guidance of the Gods." On the political front, Fela formed Movement of the People (M.O.P.) and entertained the idea of becoming a democratically elected president of Nigeria.

The spiritual revelation precipitated the name change of his group form Africa 70 to Egypt 80, and he slowed the Afrobeat groove to a more meditative pace and mellower mood and generally referred to it as 'African music' thereafter. While his musical output in the early 80s was also slowed and his skepticism of record companies grew, he struck up a trusted relationship with Linton Kwesi Johnson's musical partner, Dennis Bovell, who recorded Fela Live In Amsterdam for release on EMI in 1983.

Bovell also recorded the original tracks for Fela's ill-fated Army Arrangement, which was completed by Bill Laswell at the urging of Fela's manager Pascal Imbert, while Fela was detained in Ikoyi and later Kiri-Kiri prison on a trumped up currency smuggling charge. Since Fela had received so much recognition as a result of his imprisonment, the album was widely exposed, but without Fela's consent. "It was an idea I had to get Fela to play with new sounds, but not to change his composition," explains Bovell. "I just wanted him to play what he played, but with new equipment. Those guys, they didn't understand. As I told them, 'you wait till I finish with LKJ [and I'll finish the album]. They were like 'we gotta go now, man. The iron's hot, we gotta strike.' -- total record company shit. They changed the whole shit to what they thought was new. And they fucked it up. [When] they snuck a tape recorder into the prison, and they played it to [Fela], he was like, "Motherfucker! Who's that!?' Especially when he heard Bernie Worrell replace his own organ solo he was deeply pissed. 'Take that off. Take that off! I don't want to hear it!'"

Fela was released from the internationally publicized prison term in 1986 after eighteen months. He toured the US several times, slowly fell out of circulation and withdrew to himself and his communal circle at the Ikeja Street residence in Lagos. Fela would only release half a dozen more albums (half of what he recorded with Bovell remains in the can). In his final years, Fela continued to play at The [new] Shrine, but the recordings tapered off. "The thing that bothers me more than anything is that before Fela transcended, he was doing a new music," says Sandra. "And that music was never recorded. Maybe that music was not for the world to hear. Only for a few. He just felt like he didn't need anyone to exploit his music, so he refused to record. Fela even told me in 1991, 'why even bother?' I've said everything. It's all been said. It's all been done.'"

Fela's back catalog of over 75 albums remains largely out of circulation with only nine legitimate CDs on the market: four from Shanachie (Black Man's Cry, Original Sufferhead, Beast of No Nation and O.D.O.O.) and five from Stern's Africa (The 69 Los Angeles Sessions, Fela's London Scene, Open & Close, He Miss Road, and Underground System). Randall Grass of Shanachie Entertainment says that many offers were made on Fela's back catalog while he was alive, but nothing came of it. As Dennis Bovell explains, "Motown came to see him, and he refused. They only offered him a million dollars [for his catalog], and he thought 'hey, shit, no. I wipe my ass with a million dollars. That's my toilet paper bill!'"

Fela briefly found his way into international headlines again in 1993 when a dead body was found near his house. He was arrested, charged with murder, but eventually released. It would blur into the latter part of the list of an alleged 356 trips to court in 25 years.