Myspace Layouts - Myspace Editor

Generate your own contact table!

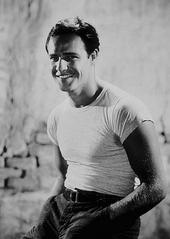

I SUPPOSE THE STORY OF MY LIFE IS A SEARCH FOR LOVE, BUT MORE THAN THAT, I HAVE BEEN LOOKING FOR A WAY TO REPAIR MYSELF FROM THE DAMAGES I SUFFERED EARLY ON AND TO DEFINE MY OBLIGATIONS, IF I HAD ANY, TO MYSELF AND MY SPECIES. WHO AM I? WHAT SHOULD I DO WITH MY LIFE? THOUGH I HAVEN'T FOUND ANSWERS, IT'S BEEN A PAINFUL ODYSSEY, DAPPLED WITH MOMENTS OF JOY AND LAUGHTER.

I was born Marlon Brando Jr. on April 3rd, 1924, in the Omaha Maternity Hospital, Nebraska, to Marlon Brando Sr and Dorothy Pennebaker. I rounded out the family and made it complete: my older sister, Jocelyn, was almost five when I was born, my sister Frances almost two. Each of us had nicknames: my mother's was Dodie, my father's Bowie, although he was Pop to me and Poppa to my sisters, Jocelyn was Tiddy, Frances was Frannie and I was Bud.

Both my sisters contrived to leave the Midwest for New York City. I managed to escape the vocational doldrums forecast for me by my cold, distant father and my disapproving schoolteachers by striking out for The Big Apple in 1943, following Jocelyn into the acting profession. Acting was the only thing I was good at, for which I actually received praise, so I was determined to make it my career.

Acting was a skill I honed as a child, the lonely son of alcoholic parents. With my father away on the road, and my mother frequently intoxicated to the point of stupefaction, I would play-act for her to draw her out of her stupor and to attract her attention and love. My mother was exceedingly neglectful, but I loved her, particularly for instilling in me a love of nature. Sometimes I had to go down to the town jail to pick up my mother after she had spent the night in the drunk tank and bring her home, events that traumatized me but may have been the grain that irritated the 'oyster of my talent'. Anthony Quinn, my co-star in 'Viva Zapata!' (1952) once told my first wife Anna Kashfi, "I admire Marlon's talent, but I don't envy the pain that created it." When you're a child who is unwanted or unwelcome, and the essence of what you are seems to be unacceptable, you look for an identity that will be acceptable.

ON MY SISTERS, JOCELYN & FRANCES....

I was always very close to my sisters because we were all scorched, though perhaps in different ways, by the experience of growing up in the furnace that was our family. We each went our own way, but there has always been the love and intimacy that can be shared only by those trying to escape in the same lifeboat. Tiddy probably knows me better than anyone else.

ON THE EARLY STAGE AND SCREEN YEARS....

I enrolled in Erwin Piscator's Dramatic Workshop at New York's New School, and was mentored by Stella Adler, a member of a famous Yiddish Theatre acting family. Adler helped introduce to the New York stage the "emotional memory" technique of Russian theatrical actor, director and impresario Constantin Stanislavsky, whose motto was "Think of your own experiences and use them truthfully." I made my debut on the boards of Broadway on October 19, 1944, in "I Remember Mama," a great success. As a young Broadway actor, I was invited by talent scouts from several different studios to screen-test for them, but I turned them down because I would not let myself be bound by the then-standard seven-year contract. I made my film debut quite some time later in Fred Zinnemann's 'The Men' (1950) for producer Stanley Kramer, playing a paraplegic soldier. Shortly afterwards, director Elia Kazan suggested me for the part of Stanley Kowalski in the production of Tennessee Williams' play 'A Streetcar Named Desire'. Kazan had directed me to great effect in Maxwell Anderson's play "Truckline Café," in which I co-starred with Karl Malden, who was to remain a close friend for the next 60 years.

ON JAMES DEAN....

After we met on the set of 'East of Eden', Jimmy began calling me for advice or to suggest a night out. We talked on the phone and ran into each other at parties, but never came close. I think he regarded me as a kind of older brother or mentor, and I suppose I responded to him as if I was. I felt a kinship with him and was sorry for him. He was hypersensitive, and I could see in his eyes and in the way he moved and spoke that he had suffered a lot. He was tortured by insecurities, the origin of which I never determined, though he said he'd had a difficult childhood and a lot of problems with his father. We can only guess what kind of actor he would have become in another twenty years. I think he could have become a great one. Instead he died and was forever entombed in his myth.

ON MARILYN MONROE....

Marilyn was a sensitive, misunderstood person, much more perceptive than was generally assumed. She had been beaten down, but had a strong emotional intelligence - a keen intuition for the feelings of others, the most refined type of intelligence. After that first visit, we had an affair and saw each other intermittently until she died in 1962. She often called me and we would talk for hours, sometimes about how she was beginning to realize that Strasberg and other people were trying to use her. The last time I spoke to her was two or three days before she died. I would have sensed something was wrong if thoughts of suicide were anywhere near the surface of Marilyn's mind. I would have known it. Maybe she died because of an accidental drug overdose, but I have always believed that she was murdered.

ON MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.....

When the civil rights movement took shape in the late fifties and early sixties, I did whatever I could to support it and went down South with Paul Newman, Virgil Frye, Tony Franciosa and other friends to join the freedom marches and be with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. At the March on Washington, I stood a few steps behind when he gave his 'I Have a Dream' speech, and it still reverberates in my mind. He was a man I deeply admired. I've always thought that while a part of him regretted having to become so deeply involved in the cause of racial equality, another part of him drove him to it, though I'm convinced he knew he would have to sacrifice himself. His bravery and courage in the face of imminent disaster still move me.'

ON MALCOLM X....

He was a dynamic person, a very special human being, who might have caused a revolution. He had to be done away with. The American government couldn't let him live. If the twenty three million blacks found a charismatic leader like he was, they would have followed him. The powers that be could not accept that.

ON THE PLIGHT OF THE NATIVE AMERICAN INDIANS....

What astonishes me is how ignorant most Americans are about the Indians and how little sympathy and understanding there is for them. It puzzles me that most people don't take seriously the fact that this country was stolen from the Native Americans, Christ Almighty, look at what we did in the name of democracy to the American Indian. We just excised him from the human race. We had 400 treaties with the Indians and we broke every one of them. It just makes me roar with laughter when I hear Nixon or Westmoreland or any of the rest of them shouting about our commitments to people and how we keep our word when we break it to the Indians every single day, led by this Senator Jackson from Washington State, perhaps the blackest figure in Indian history, who votes against giving the Indians back the lakes and fishing rights that treaties clearly entitled them to.

When they laid down their arms, we murdered them. We lied to them. We cheated them out of their lands. We starved them into signing fraudulent agreements that we called treaties which we never kept. We turned them into beggars on a continent that gave life for as long as life can remember. And by any interpretation of history, however twisted, we did not do right. We were not lawful nor were we just in what we did. For them, we do not have to restore these people, we do not have to live up to some agreements, because it is given to us by virtue of our power to attack the rights of others, to take their property, to take their lives when they are trying to defend their land and liberty, and to make their virtues a crime and our own vices virtues.

ON THE ISLAND OF TETI'AROA, TAHITI....

The happiest moments of my life have been in Tahiti. If I've ever come close to finding genuine peace, it was on my island among the Tahitians. Tahiti has exerted a force over me since I was a teenager. During a break in the filming of 'Mutiny on the Bounty', I climbed one of the tallest mountains on the island along with a Tahitian friend. At the top, he pointed to the north and said, "Can you see that island out there?" I couldn't see anything. He added "Don't you see that little island out there? It's called Teti'oroa." As we approached the island later by plane, I realized that the thin sliver of land I'd seen from afar was larger than I thought and more gorgeous than anything I had anticipated.

When I lie on the beach there naked, which I do sometimes, and I feel the wind coming over me and I see the stars up above and I am looking into this very deep, indescribable night, it is something that escapes my vocabulary to describe. Then I think: 'God, I have no importance. Whatever I do or don't do, or what anybody does, is not more important than the grains of sand that I am lying on, or the coconut that I am using for my pillow.' So I really don't think in the long sense.'

ON HOLLYWOOD AND THE IDEA OF 'CELEBRITY'....

'It's true that I always hated conformity because it breeds mediocrity, but the real source of my reputation as a rebel was my refusal to follow some of the normal Hollywood rules. The only reason I'm in Hollywood is that I don't have the moral courage to refuse the money. Success has made my life more convenient because I've been able to make some dough and pay my debts and alimony and things like that. But it hasn't given me a sense of joining that great American experiment called democracy. I somehow always feel violated. Everybody in America and most of the world is a hooker of one type or another. I guess it behooves an expensive hooker not to cast aspersions on the cut-rate hookers, but this notion of exploitation is in our culture itself. We learn too quickly the way of hookerism. Personality is merchandised. Charm is merchandised. And you wake up every day to face the mercantile society.

ON ACTING....

Acting is the least mysterious of all crafts. Everybody acts, whether it's a toddler who quickly learns how to behave to get its mother's attention, or a husband and wife in the daily rituals of a marriage, with all the artifices and role-playing that occur in a conjugal relationship. A lot of the old movie stars couldn't act their way out of a box of wet tissue paper, but they were successful because they had distinctive personalities. They were predictable brands of breakfast cereal: on Wednesdays we had Quaker Oats and Gary Cooper; on Fridays we had Wheaties and Clark Gable. They were off-the-shelf products you expected always to be the same, actors and actresses with likable personalities who played themselves more or less the same role the same way every time out.

Acting is as old as mankind. We even see it among gorillas, who know how to induce rage and whose physical postures very often determine the reaction of other animals. No, acting wasn't invented with the theatre. We know all too well how politicians are actors of the first order. That's been demonstrated by their behaviour as shown in the Pentagon papers. We should really call all politicians actors.

ON ELIA KAZAN....

On 'Streetcar' - first the play, then the movie - I discovered he was the rarest of directors, one with the wisdom to know when to leave actors alone. He understood intuitively what they could bring to a performance and he gave them freedom. Then he manicured the scene, pushed it around and shaped it until it was satisfactory. I have worked with many movie directors - some good, some fair, some terrible. Kazan was the best actors' director by far of any I've worked for.

ON BECOMING STANLEY KOWALSKI IN 'A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE'....

The problem with casting me as Stanley was that I was much younger than the character as written by Williams. However, after a meeting with Williams, he eagerly agreed that I would make an ideal Stanley. Williams believed that by casting a younger actor, the Neanderthalish Kowalski would evolve from being a vicious older man to someone whose unintentional cruelty can be attributed to his youthful ignorance. I ultimately was dissatisfied with my performance, though, saying I never was able to bring out the humor of the character, which was ironic as my characterization often drew laughs from the audience at the expense of Jessica Tandy's Blanche Dubois. During the out-of-town tryouts, Kazan realized that my portrayal was attracting attention and audience sympathy away from Blanche to Stanley, which was not what the playwright intended. The audience's sympathy should be solely with Blanche, but many spectators were identifying with Stanley. Kazan queried Williams on the matter, broaching the idea of a slight rewrite to tip the scales back to more of a balance between Stanley and Blanche, but Williams demurred. For my part, I believed that the audience sided with my Stanley because Tandy was too shrill. I thought Vivien Leigh, who played the part in the movie, was ideal, as she was not only a great beauty but she WAS Blanche Dubois, troubled as she was in her real life by mental illness and nymphomania.

ON BEING CALLED A 'REBEL'....

The closer you come to the successful portrayal of a character, the more people mythologize about you in that role. Perception is everything. I didn't wear jeans as a badge of anything, they were just comfortable. But because I wore blue jeans and a T-shirt in 'Streetcar' and rode a motorcycle in 'The Wild One', I was considered a rebel.

ON BECOMING JOHNNY STRABLER IN 'THE WILD ONE'....

'The Wild One', my fifth picture, was based on a real incident, a motorcycle gang's terrorizing of a small Californian farm town. I had fun making it, but never expected it to have the impact it did. None of us in the picture ever imagined that it would instigate or encourage youthful rebellion. If anything, the reaction to the picture said more about the audience than it did about the film. A few nuts even claimed that 'The Wild One' was part of a Hollywood campaign to loosen our morals and incite young people to rebel against their elders. Sales of leather jackets soared. In this film we were accused of glamorizing motorcycle gangs, whose members were considered inherently evil, with no redeeming qualities. As I've grown older I've realized that no people are inherently bad, including the bullies portrayed in 'The Wild One'. The public's reaction to 'The Wild One' was, I believe, a product of its time and circumstances. It was only seventy-nine minutes long, short by modern standards, and it looks dated and corny now; I don't think it has aged well. More than most parts I've played in the movies or onstage, I related to Johnny, and because of this, I believe I played him more sensitive and sympathetic than the script envisioned. There's a line in the picture where he snarls, 'Nobody tells me what to do.' That's exactly how I've felt all my life. Like Johnny, I have always resented authority.

ON 'THE METHOD'....

Some people have said my appearance as Stanley on stage and on screen revolutionized American acting by introducing "The Method" into American consciousness and culture. Method acting, rooted in Adler's study at the Moscow Art Theatre of Stanislavsky's theories that she subsequently introduced to the Group Theatre, was a more naturalistic style of performing, as it engendered a close identification of the actor with the character's emotions. Adler took first place among my acting teachers, and socially she helped turn me from an unsophisticated Midwestern farm boy into a knowledgeable and cosmopolitan artist. I don't like the term "The Method," which quickly became the prominent paradigm taught by such acting gurus as Lee Strasberg at the Actors Studio. Strasberg was a talentless exploiter who claimed he had been my mentor. Instead I've credited my knowledge of the craft to Stella and Kazan. Stella's method emphasized that authenticity in acting is achieved by drawing on inner reality to expose deep emotional experience.

I've had good years and bad years and good parts and bad parts and most of it's just crap. Acting has absolutely nothing to do with being successful. Success is some funny American phenomenon that takes place if you can be sold like Humphrey Bogart or Marlon Brando wristwatches. When you don't sell, people don't want to hire you and your stock goes up and down like it does on the stock market.

ON BECOMING TERRY MALLOY IN 'ON THE WATERFRONT'....

After 'Streetcar', I appeared in 'Viva Zapata!' (1952), 'Julius Caesar' (1953) and Kazan's 'On the Waterfront' (1954). For my portrayal of Terry Malloy, I won my first Oscar. The cast included my longtime friend Karl Malden, Eva Marie Saint, Lee J. Cobb, and Rod Steiger. People have often commented to me about the scene in 'On The Waterfront' that takes place in the backseat of a taxi. I played Rod Steiger's unsuccessful ne'er-do-well brother, and he played a corrupt union leader who was trying to improve my position with the Mafia. He had been told in so many words to set me up for a hit because I was going to testify before the Waterfront Commission about the misdeeds that I was aware of. In the script, Steiger was supposed to pull a gun in the taxi, point it at me and say, 'Make up your mind before we get to 437 River Street,' which was where I was going to be killed. I told Kazan, 'I can't believe he would say that to his brother, and the audience is certainly not going to believe that this guy who's been close to his brother all his life, and who's looked after him for thirty years, would suddenly stick a gun in his ribs and threaten to kill him. It's just not believable.' We did the scene Kazan's way several times, but I kept saying, 'It just doesn't work, Gadg, it really doesn't work.' Finally he said, 'All right, wing one.' So Rod and I improvised the scene and ended up changing it completely. Gadg was convinced and printed it. When the movie came out, a lot of people credited me with a marvelous job of acting and called the scene moving. But it was actor-proof, a scene that demonstrated how audiences often do much of the acting themselves in an effectively told story. It couldn't miss because almost everyone believes he could have been a contender, that he could have been somebody if he'd been dealt different cards by fate, so when people saw this in the film, they identified with it. That's the magic of theater; everybody in the audience became Terry Malloy, a man who'd had the guts not only to stand up to the Mob, but to say, 'I'm a bum. Let's face it; that's what I am....'

ON STELLA ADLER....

Stella always said no one could teach acting, but she could. She had a knack for teaching people about themselves, enabling them to use their emotions and bring out their hidden sensitivity. Her instincts were unerring and extraordinary. When I met her, she was about forty-one, quite tall and very beautiful, with blue eyes, stunning blond hair and a leonine presence, but a woman much disappointed by what life had dealt her. She was a marvelous actress who unfortunately never got a chance to become a great star, and I think this embittered her. But while she never fulfilled her dream, she left an astounding legacy. Virtually all acting in motion pictures today stems from her, and she had an extraordinary effect on the culture of her time.

ON WORK IN THE 1960s....

The rap on me in the 1960s was that I had ruined my potential to be America's answer to Laurence Olivier. People said that by failing to go back to stage, something British actors such as Richard Burton were not afraid to do, I had stifled my 'great talent' by refusing to tackle the classical repertoire and contemporary drama. I believe I did some of my best acting of my life in films such as 'Burn!', but critics thought otherwise. Most people in the 1960s believed that I needed to be reunited with my old mentor Kazan. I originally accepted an offer to appear as the star of Kazan's film adaptation of his own novel, 'The Arrangement' (1969). However, after the assassination of Martin Luther King, I backed out of the film, telling Kazan that I could not appear in a Hollywood film after this tragedy. I also turned down the role opposite Paul Newman in a script, 'Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kind' (1969), and decided instead to make 'Queimada' (1969) with Gilo Pontecorvo. It was a searing indictment of racism and colonialism, which won the esteem of progressive critics, but because it failed at the box office, it was not seen as a great film.

People ask that a lot. They say, 'What did you do while you took time out ?' - as if the rest of my life is taking time out. But the fact is, making movies is time out for me because the rest, the nearly complete whole, is what's real for me. I'm not an actor and haven't been for years. I'm a human being - hopefully a concerned and somewhat intelligent one - who occasionally acts.

ON BECOMING PAUL IN 'LAST TANGO IN PARIS'....

I followed my portrayal of Don Corleone with my turn in 'Ultimo tango a Parigi' (1972), the first film dealing explicitly with sexuality. I was now again a 'Top-Ten box office star'. I find it depressing that a film's success is based on how much it grosses at the box office. I thought I did some of my best acting in the projects I participated in through the 1960s, such as 'Burn!', which were only to be excoriated and ignored as the films did not do well at the box office. Essentially, I was through with the movies and their backward nature of accolade.

ON BECOMING 'THE GODFATHER'....

For 'The Godfather' (1972), a young Francis Ford Coppola believed there was only one actor who could play godfather to the group of Young Turk actors he had assembled for his film. I went home and did some rehearsing to satisfy my curiosity about whether I could play an Italian. I put on some makeup, stuffed Kleenex in my cheeks, and worked out the characterization first in front of a mirror, then on a television monitor. After working on it, I decided I could create a characterization that would support the story. The people at Paramount saw the footage and liked it, and that's how I became the Godfather. I'd gotten to know quite a few mafiosi, and all of them told me they loved the picture because I had played the Godfather with dignity. Even today I can't pay a cheque in Little Italy.

I don't think the film is about the Mafia at all. I think it is about the corporate mind. In a way, the Mafia is the best example of capitalists we have. Don Corleone is just an ordinary American business magnate who is trying to do the best he can for the group he represents and for his family. I think the tactics the Don used aren't much different from those General Motors used against Ralph Nader. Unlike some corporate heads, Corleone has an unwavering loyalty for the people that have given support to him and his causes and he takes care of his own. He is a man of deep principle and the natural question arises as to how such a man can countenance the killing of people. But the American Government does the same thing for reasons that are not that different from those of the Mafia. And big business kills us all the time with cars and cigarettes and pollution and they do it knowingly.'

ON JFK....

When JFK ran for president, I believed he was a new kind of politician whom I could admire. He was not only charming but bright, and he had a sense of history and curiosity and an apparent sincerity about wanting to right some of the wrongs in our country. At a fund raising dinner I attended, Kennedy began working the room, table-hopping and shaking hands with everyone. After dinner a Secret Service agent came over and told me the president wanted to see me, so I followed the man upstairs to Kennedy's hotel room. Kennedy was unbridled, spirited and full of zest and curiosity about the women I knew in Hollywood. Changing the subject, he said, 'You're getting too fat for the part.' I said, 'What part? Are you kidding? Have you looked in the mirror lately? Your jowls won't even fit in the frame of the television screen.' Kennedy said he weighed a lot less than I did, so we headed for the bathroom, both of us weaving, and I got on the scale. I can't remember what my weight was, but when he got on it I put my toe on the corner and made him about twenty-five pounds heavier, so that he weighed more than I did. 'Let's go, Fatso, you lost,' I said.

ON MONTGOMERY CLIFT....

We were both from Omaha and broke into acting about the same time. We had the same agent, Edie Van Cleve, and although he was four years older than me, we were sometimes described as rivals for the same parts. There may have been a rivalry between us...but I don't remember ever feeling that way about him. In my memory he was simply a friend with a tragic destiny. There was a quality about Monty that was very endearing; besides a great deal of charm, he had a powerful emotional intensity, and like me, he was troubled, something I empathized with. When Monty showed up in Paris for 'The Young Lions', he was consuming more alcohol than ever. His face was gray and gaunt, and he had lost a lot of weight. I saw he was on the trajectory to personal destruction and talked to him frankly, opening myself completely to him. I tried to shore him up and did the best I could to get him through the picture, but afterwards his descent continued until he died in 1966 at the age of forty-six. He carried around a heavy emotional burden and never learned how to bear it.

ON ANNA MAGNANI...

Tennessee Williams and Sidney Lumet invited me to be in the movie 'The Fugitive Kind', which was based on Williams' play 'Orpheus Descending'. I played a guitar-playing drifter who wandered into a small town in Mississippi and got involved with an older woman, played by Anna, who had been a powerful actress in the Italian film 'Open City' and later in Tennessee's movie 'The Rose Tattoo'. Tennessee warned me that Anna, who was sixteen years older than me and had a reputation for enjoying the company of young men, had told him that she was in love with me, and before we left for upstate New York to film the picture she confirmed it. After we had some meetings in California, she tried several times to see me alone, and finally succeeded one afternoon at the Beverly Hills Hotel. Without any encouragement from me, she started kissing me with great passion. Once she got her arms around me, she wouldn't let go. If I started to pull away, she held on tight and bit my lip. With her teeth gnawing at my lower lip, the two of us locked in an embrace, I was reminded of one of those fatal mating rituals of insects that end when the female administers the coup de grace. Finally the pain got so intense that I grabbed her nose and squeezed it as hard as I could, as if I were squeezing a lemon, to push her away. It startled her, and I made my escape.

ON VIVIEN LEIGH....

In many ways she was Blanche. She was memorably beautiful, one of the great beauties of the screen, but she was also vulnerable, and her own life had been very much like that of Tennessee's wounded butterfly.

ON THE OSCAR EXPERIENCE....

I had a great conflict about going to the Academy Awards and accepting an Oscar. I never believed that the accomplishment was more important than the effort. I remember being driven to the Awards still wondering whether I should have put on my tuxedo. I finally thought, what the hell; people want to express their thanks, and if it is a big deal for them, why not go? I have since altered my opinion about awards in general, and will never again accept one of any kind.

When I was nominated for 'The Godfather', it seemed absurd to go to the Awards ceremonies. Celebrating an industry that had systematically misrepresented and maligned American Indians for six decades, while at the moment two hundred Indians were under siege at Wounded Knee, was ludicrous. Still, if I did win an Oscar, I realized it could provide the first opportunity in history for an American Indian to speak to sixty million people - a little payback for years of defamation by Hollywood. I think awards in this country at this time are inappropriate to be received or given until the condition of the American Indian is drastically altered. If we are not our brother's keeper, at least let us not be his executioner.

ON CHARLIE CHAPLIN....

Chaplin you got to go with. Chaplin is a man whose talents is such that you have to gamble. First off, comedy is his backyard. He's a genius, a cinematic genius. A comedic talent without peer. You don't know that he's senile.

ON THE CLASSICAL THEATER...

I've heard it said that I should have devoted my life to the classical theater as Olivier did. If I had wanted to be a great actor, I agree that I should have played Hamlet, but I never had that goal or interest. I have never had the actor's bug. I took acting seriously because it was my job; I almost always worked hard at it, but it was simply a way to make a living. Still, even if I had chosen to go on the classical stage, it would have been a mistake. I revere Shakespeare, the English language and English theater, but American culture is simply not structured for them. Theatrical ventures ambitious enough to accomplish something truly worthwhile seldom survive. The British are the last English-speaking people on the planet who love and cherish their language. They preserve it and care about it, but Americans do not have the style, finesse, refinement or sense of language to make a success out of Shakespeare. Our audiences would make a pauper of any actor who dedicated his career to Shakespeare. Ours is a television and movie culture.

(All taken from Songs My Mother Taught Me)

IN THE WORDS OF GEORGE ENGLUND, MY GOOD FRIEND & MENTOR...

Looking at Marlon only as an actor, he dominates the twentieth century the way Picasso dominates painting. Other actors were excellent and performed with beauty and riveted audiences with their skills. There were fine schools of acting and fine teachers, the Group Theater, the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, the Juillard, Sanford Meisner, Stella Adler. But, Marlon rode his chariot above all these fiefdoms. Actors, absorbed in their traditions and orthodoxies, looked up to see a new king. And he was so young, so primitive, so imperial...With the advent of Marlon, pretty much all other views of acting went slack and actors herded around and tried to be like Marlon Brando. He didn't read his lines, he didn't memorize his lines, he didn't start with lines. He started with who he was and what he was feeling. He was open to the moment, to the look, the behavior, the certainty or lack of it in the actors with him. He didn't come to rehearsal with an organized plan the way Olivier did, he listened and watched and then he knew what he wanted to do. There were no rules for him, in acting or in life. Everything was open to observation, assimilation, and use. Never mind the questionable choices Marlon made later in life, the way it seemed to some that he frittered away his magnificent talents. Which artist has walked a straight and sensible road his whole life? When he was at his best, Marlon was the best.