I edited my profile with Thomas' Myspace Editor V4.4

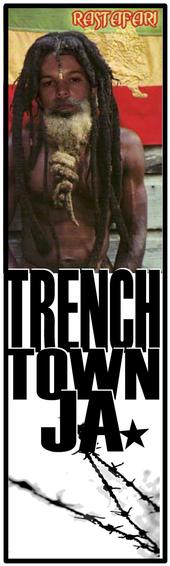

Trenchtown: A Spiritual Powerpoint

Eddie BrannanThe island of Jamaica is about the size of Long Island, its capital, Kingston, is approximately the size of Brooklyn, and the neighborhood of Trenchtown would fit into a few square New York City blocks. Yet despite its size, this tiny quarter has had a tremendous impact on late-20th century aesthetics, and continues to do so into the 21st century, through music, film and fashion.

The style, the attitude and in particular the reggae music that has come out of Trenchtown has quite literally transformed the topography of contemporary popular culture.

Trenchtown, in West Kingston, was originally built as a housing project, replacing squatter camps that were destroyed by hurricane Charlie in 1951. Despite the poverty and violence that plagued Trenchtown from its beginnings it was considered desirable accommodation for the shantytown dwellers who typically came to Kingston from rural Jamaica to seek work. The new development’s housing units consisted of one- or two-story concrete buildings, arranged around a central courtyard with communal cooking facilities and a stand-pipe for water. No sewage system was installed in Trenchtown. Before the hurricane, the squatter camps had emerged around Kingston’s garbage dump.

Many of the shantytown residents were ragpickers, and it was considered a locale of outcasts. It had also become the home of one of Kingston’s Rastafarian communities. They considered the place to be, in the words of senior Rasta Mortimer Planner (who moved there in 1939), a “spiritual powerpoint.†Planner, who had greeted Emperor Haile Selassie when he visited Jamaica, was later to serve as mentor and guru to the man who became Trenchtown’s most prominent resident, Bob Marley, whose mother moved her family there from rural Nine Miles in 1957. The radical politics and spirituality of Marley’s music are the product of his Trenchtown upbringing, and in particular they reflect the turmoil and violence that plagued the neighborhood from the early 1970s onwards.

During this period the two main rival Jamaican political parties—the People’s National Party and the Jamaica Labour Party, both known by their intials—sponsored Kingston neighborhood “dons†to enforce their dominance in the communities, ensuring that only their party’s supporters had access to jobs and services. Trenchtown’s don, and therefore Trenchtown, was PNP, which put it at war with neighboring Rima, a JLP stronghold. The road between the two, which appears on page 51 of this book, was the frontline in an all-out war. In time the dons outgrew the controlling influence of their political masters and turned to drug trafficking and extortion, and Trenchtown, like other parts of downtown Kingston, was carved up into warring gang territories.

As this transformation took place the archetype of the Trenchtown resident also changed; the spiritual Rastaman, the “sufferer†stolidly enduring in “Babylon,†was replaced by a different model, the authority-flouting, gun-toting, fearless “rudeboy.†Trenchtown became a place where shootouts were frequent, where young men slept in shifts to avoid being ambushed by rivals, where young women were in frequent danger of rape by men or acid attacks by women, where lawlessness prevailed, and where Kingstonians from the better parts of town feared to venture.

Yet despite Trenchtown’s fearsome reputation it is still a community. Children are born here, families are raised here, and some of the people of Trenchtown are working to elevate the neighborhood above its problems. The Trenchtown Reading Association was formed in 1993 to encourage literacy amongst local children, later moving to larger premises and establishing a pre-school in the community.

The Trenchtown Development Association was established in 1996 to encourage government spending and services in the neighbor-hood. And of course art is made here; over the decades, Trenchtown has remained a vibrant cultural center. The list of significant musicians that have emerged from Trenchtown is remarkable given the size of the place, and includes original luminaries like Alton Ellis, Bunny Wailer, Peter Tosh and of course Marley; and the style of the rudeboys, their shaped and patterned haircuts, their ability to make a bold fashion statement from items as basic as a string vest and bandana, has been an influence on youths worldwide.

Trenchtown Love, Patrick Cariou’s third monograph, attempts to paint as broad and as honest a picture of Trenchtown as is possible for an outsider. It was a long-standing ambition of his to shoot here, and he originally conceived the book as a photo essay on rudeboys. It was to be a counterpoint to his last work, Yes Rasta, which was shot amongst the Rastamen living a totally “ital†spiritual and pure life in the rural hills of Jamaica.

The first time he tried to photograph a Kingston rudeboy, however, he was shot at, and swiftly shelved his plans. However a chance meeting with a Trenchtown don, visiting relatives in Cariou’s Fort Greene, Brooklyn neighborhood, led to an invitation to return to Trenchtown to document the neighborhood, resulting in the images in this book. Cariou’s last two books, Surfers and Yes Rasta, focused upon men who have chosen alternative, often secluded lifestyles, consumed by ritual and to a large extent shrouded in mystery. And as this book was conceived, Trenchtown Love might have followed a similar path.

But the circumstances of its creation, as well as the conflicting impressions Cariou received while there, made it something quite different. In the first place, being from Trenchtown is not a calling or a lifestyle one chooses to adopt. It is a circumstance arising from poverty and hardship.

Perhaps that is why these images are quite different from the photographs of the dreads and surfers. These men and women and children are not the ascetics of the previous books, surrounded by sublime land and seascapes. They are human beings, scrabbling to get by in a very hard place and Cariou, sensing this, has made images that get far closer to his subjects, embrace far more of their good, bad and indifferent humanity. These are “true†portraits; they tell their subjects’ stories, report on their lives, and do so accompanied by the photographer’s clear and consistent personal narrative. The bravado, posturing, frankness, apathy, strength and dignity that Cariou has documented is as often unsettling as it rewarding; he hasn’t tried to edit or beautify what he saw.

That is the book’s strength. It isn’t a picture-postcard view of the ghetto. It is a piece of personal reportage in the form of a series of portraits, and despite the brevity of the moments that Cariou spent with his subjects, the viewer senses that he has told their stories accurately, fairly and with a Trenchtown type of love.

Patrick Cariou is a portraitist in love with strength. He is drawn to the heroic and the powerful, the men (and it is often men) who seem to represent a fierce independence, who appear to have risen above the compromises society has forced upon the rest of us. He is also an anthropologist. Surfers and Yes Rasta have as much of the ethnography about them as they do the monograph. In order to make the pictures in those books Cariou had to spend many years with his subject in order to gain their trust and for his presence to be sufficiently unobtrusive to permit the degree of candor in the photographs.

His subjects are outsiders, a class of humanity to whom Cariou finds himself perpetually drawn. Cariou is a man who enjoys the company of thugs and relishes low life. Thus the rudeboys and outcasts of Trenchtown make natural and compelling subjects for him. The fact that to shoot there is well nigh impossible for a non-resident demonstrates his dedication. For Cariou, to shoot in Trenchtown, which he describes as “the most famous ghetto in the world,†was a personal mission.

“The womb of all rudeboys,†he says, “is Trenchtown.†Cariou grew up in a small town near Quimper, in Brittany, far removed from the slums of downtown Kingston. His first aesthetic impulses arose from watching storms gathering over the beach near his home, while still a “romantic adolescent,†as he puts it. This fascination with the power and beauty of nature endures in his photography, despite his being considered a portraitist. In Paris, as a young man, he interspersed his fashion work with portraits of the young iconoclasts of the burgeoning hip-hop generation. Surfers was, for Cariou, a smooth introduction into the world of serious documentary portraiture.

The challenge was merely to get to the distant locations where serious surfers congregate and to spend time with them. Making photographs in Jamaica was a totally different, far more difficult, frustrating and troubling experience.

Nonetheless, recalls Cariou, the minute he set foot on Jamaican soil in 1996 he felt he belonged there. He says he “knew who was who and what was what; who to talk to, who to walk with, who not to, who was the tough guy, who was acting it.†Cariou has always been deeply fascinated by Jamaican culture, with reggae music and the complex set of social, geographical and political factors that created it and that it, in turn, creates. And like those who come to the island with the intention of being more than a mere tourist in the gated resorts at Negril and Ocho Rios, he was faced with the contradictions and problems that plague this beautiful, bountiful island. And through Yes Rasta and now Trenchtown Love he has offered his response.

Thus this book becomes more than merely a portfolio of the exotic, photogenic denizens of Kingston’s underbelly. Like many whose involvement with this island runs both deep and intensely personal, Cariou decries the mentality that has made this the most corrupt and the most dangerous island in the Caribbean. Cariou sees in Jamaica’s people the conflicts of their history. “A majority of the people of Jamaica are descended from warriors. They have the [strength] of warriors and rebels, but they also inherited the disposition towards egotism, exag-gerration and violence.â€

So Trenchtown Love is not a naïf’s ode to stylish, stylized desperation, and the title deliberately contains ambiguities. Just as in Scotland a “Glasgow kiss†is the ironic term for a headbutt to the bridge of the nose, the kind of love shown in Trenchtown is as much about acid thrown in someone’s face as it is about building a library, as much about guns and machetes as about bricks and mortar, as much about abnegation of responsibility as overcoming obstacles.

This, in the end, is the triumph of Cariou’s new book. “I aim to report what I experience, to understand society by the visual.†Cariou explains that both Surfers and Yes Rasta reflected the inspiration he had taken from Paul Strand and August Sander. Yet he felt it was time for a change, and further that his subject matter demanded it. “I felt I’d done my thing on classicism,†explains Cariou. “TL was the perfect vehicle to use a more aggressive, modern style. It was necessary to capture the flamboyance of Trenchtown.â€

So Trenchtown Love, Patrick Cariou’s first book in “living†color, represents both a new step and retrenchment of his attitudes and beliefs. As he says, he is a portraitist; he chooses his subjects and does not claim to be simply a reporter. Nonetheless, as Trenchtown Love clearly demonstrates, there is a fierce desire for integrity, accuracy and honesty in Cariou’s photography. “It’s very important not to betray the people I photograph,†he explains. “It’s very important that they recognize themselves in the images.†Eddie Brannan

Patrick Cariou’s photographs are features on this space