Create or get your

very own MySpace Layouts

Antoine Clark started F.E.D.S. magazine after a gang member shot him outside a Bronx roller rink in 1987. He was left paralyzed and struggling over what to do with the rest of his life.

While he was learning to walk again, he sent for one of those get-rich-quick real estate publications advertised on late night television. He couldn't follow the texts, but publishing intrigued the high-school drop-out. Clark decided to produce a magazine about something he understood intimately: the mean streets.

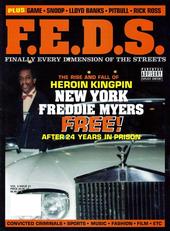

"Finally Every Dimension of the Streets," Clark's magazine, publicizes murderers, drug dealers and gang leaders as part of its self-proclaimed mission to strip street life of all illusory glamour. Instead of detracting from hustlers, however, F.E.D.S. has spawned a new publishing genre -- "gangsta mags" -- complete with unflinching new competitors.

"F.E.D.S. is not about entertainment, but deterrence," said Clark, 35, surrounded by bundles of the latest issues in his Park Avenue South office. "We show the downside of what's going on in the streets and try to scare people straight. The other magazines are imitations without the mission."

After regaining his legs, Clark took $7,000 he made from getting a rap act a record deal and published 5,000 copies of F.E.D.S. in November 1998. The first issue was a rough 16-page handout featuring convicts and hustlers. He dropped them off at Harlem newsstands, and they immediately sold out.

Soon, he had a street-corner public clamoring for the next issues. It was only a matter of time before F.E.D.S. found its way into prisons, sometimes as photocopies being passed from cell to cell. Clark has since been inundated with subscription orders from facilities in 37 states. More than 90 percent of F.E.D.S.' 7,000 subscribers are inmates.

At $3.95 a copy, F.E.D.S.' 75,000 initial press runs sell out barely before the ink dries. Clark publishes quarterly, he said, because much of his time is taken up reprinting back issues. Now he's working on a book for Harper Collins, collecting all of F.E.D.S.' articles and writing the stories-behind-the-stories.

F.E.D.S. has featured jailhouse interviews with Nicky Barnes, the godfather of Harlem's heroin trade in the 1970s, Alberto "Alpo" Martinez, a major East Coast cocaine dealer and murderer-now-turned federal informant, and Peewee Kirkland, a New York street basketball legend who skipped the pros to make a killing dealing drugs. In between criminal confessions, F.E.D.S. covers the hardcore rap world and events in Harlem and the Bronx, including recent street killings.

Clark said he has the same criteria for all of his cover subjects. They must have been convicted and their crimes must have destroyed their lives.

"I will not publish stories of people who say they're not guilty," he said. "We're not here to give them glory, but to draw attention to the consequences of the gangster life."

Instead of gutting gangster glamour, however, F.E.D.S.' success has inspired a new generation of competitors who have fewer reservations about celebrating street life.

Criminal confessions and tales of the dark side of hip-hop life are a staple of F.E.D.S. magazine -- the name stands for ``Finally Every Dimension of the Streets.'' The interviews' gruesome authenticity has won a fast audience at Rikers Island jail, where inmates pass around photocopies.

The articles may horrify some readers, but Antoine Clark, the editor, reporter and photographer, sees them as cautionary tales -- a look at where the gangster life can lead.

F.E.D.S. is something of a sensation in the prison system, which accounts for more than 90 percent of its 7,000 paid subscribers.

On its cover, the magazine promises articles on ``convicted hustlers, street thugs, fashion, sports, music and film.''

But Clark believes his gory reporting on street violence helps deflate the criminal myths promoted by some rap stars.

``I want to show the other side of this life,'' he said. ``I want to show what happens to these gangsters when things go wrong, as they almost always do.''

F.E.D.S. reports off the streets of Harlem and the Bronx in a way other magazines like Source, Vibe and Blaze do not. In addition to criminal confessions, F.E.D.S. prints the doings of the hottest hip- hop artists and what's going on in the neighborhoods, all spewed out in raw slang. Each issue of the quarterly sells out within a few days of hitting newsstands.

Clark, 35, calls news sources on a cell phone in the old car that is his office, and he gets his mail at a post office box. He carries around stacks of letters from prison, most with government-issued checks from correctional facility accounts, demanding copies of the three preceding issues of the magazine, a demand he is unable to meet because there are no copies left.

But he is not eager to anger a readership that has a history of violent behavior, so he is planning to reprint all the past cover articles in an issue scheduled for next week.

``I wanted to show what was real, what was going on,'' Clark said. ``No one was doing that. I've seen these people get killed off one after the other. I know how these big criminals in prison cry at Christmas and at night because they are alone. It seemed time to tell about real life and tell about it in the language people use.''

The magazine, with glossy color photos, is rough-edged in its use of language, but it shows what tenacity and persistence can achieve. Clark, who is never without his camera and tape recorder, has written detailed articles about big-time criminals in Harlem and the Bronx, including a long article on Nicky Barnes, known as the Black Godfather, a heroin kingpin of the 1970s. Barnes was convicted of federal narcotics violations and in 1978 was sentenced to life in prison without parole.

In each issue, F.E.D.S. prints an ``R.I.P.'' page for those killed in the latest street violence, as well as pictures of heroin addicts at local shooting galleries with the headline ``Drugs Kill.''

``It is a unique magazine,'' said David Mays, the owner of Source, the United States' second-largest music magazine, after Rolling Stone.