Pimp your page with Pimp My Myspace Page

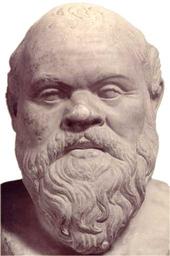

I wish to seek and share wisdom with young

people and others who wish to do the same.

In my use of critical reasoning, by my unwavering commitment to truth, and through the vivid example of my own life, fifth-century Athenian I set the standard for all subsequent Western philosophy. Since I left no literary legacy of my own, you are dependent upon contemporary writers like Aristophanes and Xenophon for your information about my life and work. As a pupil of Archelaus during my youth, I showed a great deal of interest in the scientific theories of Anaxagoras , but I later abandoned inquiries into the physical world for a dedicated investigation of the development of moral character.

Having served with some distinction as a soldier at Delium and Amphipolis during the Peloponnesian War, I dabbled in the political turmoil that consumed Athens after the War, then retired from active life to work as a stonemason and to raise my children with my wife, Xanthippe. After inheriting a modest fortune from my father, the sculptor Sophroniscus, I used my marginal financial independence as an opportunity to give full-time attention to inventing the practice of philosophical dialogue.

For the rest of my life, I devoted myself to free-wheeling discussion with the aristocratic young citizens of Athens, insistently questioning their unwarranted confidence in the truth of popular opinions, even though I often offered them no clear alternative teaching. Unlike the professional Sophists of the time, I pointedly declined to accept payment for my work with students, but despite (or, perhaps, because) of this lofty disdain for material success, many of them were fanatically loyal to him.

Their parents, however, were often displeased with my influence on their offspring, and my earlier association with opponents of the democratic regime had already made me a controversial political figure. Although the amnesty of 405 forestalled direct prosecution for my political activities, an Athenian jury found other charges—corrupting the youth and interfering with the religion of the city—upon which to convict me, and they sentenced me to death in 399 B.C.E. Accepting this outcome with remarkable grace, I drank hemlock and died in the company of my friends and disciples.

Your best sources of information about my philosophical views are the early dialogues of my student Plato , who attempted there to provide a faithful picture of the methods and teachings of his master. (Although I also appear as a character in the later dialogues of Plato, these writings more often express philosophical positions Plato himself developed long after my death.)

In the Socratic dialogues, my extended conversations with students, statesmen, and friends invariably aim at understanding and achieving virtue {Gk. areth [aretê] } through the careful application of a dialectical method that employs critical inquiry to undermine the plausibility of widely-held doctrines. Destroying the illusion that we already comprehend the world perfectly and honestly accepting the fact of our own ignorance, I believed, are vital steps toward our acquisition of genuine knowledge, by discovering universal definitions of the key concepts governing human life.

Interacting with an arrogantly confident young man in Euqufrwn ( Euthyphro ), for example, I systematically refuted the superficial notion of piety (moral rectitude) as doing whatever is pleasing to the gods. Efforts to define morality by reference to any external authority, I argued, inevitably founder in a significant logical dilemma about the origin of the good . Plato's Apologhma ( Apology ) is an account of my (unsuccessful) speech in my own defense before the Athenian jury; it includes a detailed description of the motives and goals of philosophical activity as I practiced it, together with a passionate declaration of its value for life.

The Kritwn ( Crito ) reports that during my imprisonment I responded to friendly efforts to secure my escape by seriously debating whether or not it would be right for me to do so. I concluded to the contrary that an individual citizen—even when the victim of unjust treatment—can never be justified in refusing to obey the laws of the state .

In the Menwn ( Meno ) Plato described how I tried to determine whether or not virtue can be taught , and this naturally leads to a careful investigation of the nature of virtue itself. Although my direct answer is that virtue is unteachable, I do propose the doctrine of recollection to explain why we nevertheless are in possession of significant knowledge about such matters. Most remarkably, I argue here that knowledge and virtue are so closely related that no human agent ever knowingly does evil : we all invariably do what we believe to be best.

Improper conduct, then, can only be a product of our ignorance rather than a symptom of weakness of the will {Gk. akrasia [akrásia] }. The same view is also defended in the PrwtagoraV ( Protagoras ), along with the belief that all of the virtues must be cultivated together. [Adapted from Philosophy Pages ]