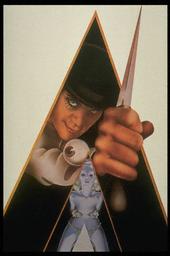

Stanley Kubrick's ninth film, A Clockwork Orange," which has just won the New York Film Critics Award as the best film of 1971, is a brilliant and dangerous work, but it is dangerous in a way that brilliant things sometimes are.

I'd hardly put it in the same category with nuclear energy, "A Declaration of Independence" and "The Interpretation of Dreams," but it is a movie of such manifold, contradictory effects that it can easily be seen in many ways and may well be wrongly used by a number of people who see it. It is an almost perfect example of the kind of New Movie that is all the more disorienting--and thus, apparently, dangerous--because it seems to remain aloof from, and uninvolved with, the matters it's about.

Somewhere during the second third of the film, Alex (Malcolm McDowell), a vicious teenage London hood who has the cheeriness of a ratty Candide, is subjected to the Ludovico Technique, a type of aversion therapy that effectively neutralizes Alex's passions for both ultra-violence and the music of lovely lovely Ludwig Van, by making him physically ill whenever these passions arise.

After some plot permutations that I need not go into, Alex is suddenly returned to his old self. While he is recovering in the hospital, he is visited by the Minister of the Interior (whom Alex calls Fred), who presents Alex with a new stereo. As the Fourth Movement from Beethoven's Ninth Symphony fills the soundtrack, Alex's eyeballs, like those of some idiot doll, roll upward in their sockets and momentarily we share another one of Alex's sado-masochistic sex fantasies: he is thrashing around in the turf at Ascot, forcibly putting the old in-out to another helpless, faceless woman, while the handsomely dressed ladies and gentlemen applaud in silence and boredom. The music stops abruptly and Alex announces triumphantly: "I was cured!"

In a movie of more conventional emotional structure, where identification with the central character has been easy and complete, we might, I suppose, share something of Alex's triumph. However, we've spent the last two hours or so being alternately amused, horrified, sickened and moved by Alex who has, among other things, beaten up an old bum; bludgeoned to death a nutty health farm lady (with a giant porno art sculpture of a penis and testicles); and then has himself been turned into a helpless vegetable by the Ludovico Treatment.

Alex's return is a return to a kind of crafty viciousness that most of us know only in the darkest corners of our souls. In other words, we can't--or shouldn't--share Alex's triumph. I am saddened--and a bit confused--for although The End flashes on the screen, that is not really the end of "A Clockwork Orange." As we walk out of the theater, and as the final credits are flashing on the screen, the theater is filled with the sound of Gene Kelly singing "Singin' in The Rain," backed by one of those fulsome old M-G-M orchestrations from the 1952 movie. The effect is that of the Ludovico Treatment gone slightly awry. Our reactions are both blissful (the recollection of the great Stanley Donen-Gene Kelly film) and, more immediately, terrifying (the memory of a scene in "A Clockwork Orange" in which Alex, doing a passable soft-shoe, kicks into semi-unconsciousness a man whose wife he is about to rape, all the while singing "Singin' in The Rain.")

A friend of mine has suggested that Kubrick was pulling a fast one by running the old Kelly recording over the end credits of the film, thereby hoping to wipe away or, at least, to diminish the frigid effect of the movie. It seems to me, however, that the point of the Arthur Freed-Nacio Herb Brown number is much more interesting--and typical of Kubrick's method throughout "A Clockwork Orange."

Although the film, like Anthony Burgess's novel from which it is adapted, is cast as futurist fiction, it is much more a satire on contemporary society (especially on British society of the late 1950s and 1960s) than are most futurist works, all of which, if they are worth anything, are meaningful only in terms of the society that bred them. It may even be a mistake to describe the movie "A Clockwork Orange" as futurist in any respect, since its made-up teenage language (Nadsat), its décor, its civil idiocies, its social chaos, or their equivalents, are already at hand, although it's still possible for most of the people who file in and out of the Cinema I on Third Avenue to ignore a lot of them.

"A Clockwork Orange" is about the rise and fall and rise of Alex in a world that is only slightly less dreadful than he is--parents, policemen, doctors and politicians are all either evil, opportunistic or simpleminded. Yet Kubrick has chosen to fashion this as the most elegantly stylized, most classically balanced movie he has ever made--and not, I think, by accident. It isn't just that the narrative comes full circle, that characters, as in something by Dickens, met early, show up by chance later on, that he final resolution returns us to the beginning to make the ending just that much more bleak.

It's also because every moment of unspeakable horror is wrapped in cool beauty, either through Kubrick's camera eye, or by music on the soundtrack. When Alex and his droogs come upon the rival Billyboy's gang, preparing to rape a helpless devotchka in (Alex tells us on the soundtrack) "the old derelict casino," we begin the scene with a close-up of a lovely faded rococo fresco at the top of the proscenium of the casino stage (music by Rossini), before we pan down to the mayhem below. There is even beauty in this voice- over narration, in the words of Nadsat and in the Elizabethan syntax occasionally affected by Alex and his friends.

It seems to me that by describing horror with such elegance and beauty, Kubrick has created a very disorienting but human comedy, not warm and lovable, but a terrible sum- up of where the world is at. With all of man's potential for divinity through love, through his art and his music, this is what it has somehow boiled down to: a civil population terrorized by hoodlums, disconnected porno art, quick solutions to social problems, with the only "hope" for the future in the vicious Alex.

It is hardly a cheery thought, which is why the sound of Gene Kelly singing "Singin' in The Rain" as we leave the theater is so disconcerting. It's really a banana peel for the emotions.

"A Clockwork Orange" might correctly be called dangerous only if one doesn't respond to anything else in the film except the violence. One critic has suggested that Kubrick has attempted to estrange us from any identification with Alex's victims so that we can enjoy the rapes and the beatings. All I can say is that I did not feel any such enjoyment. I was shocked and sickened and moved by a stylized representation that never, for a minute, did I mistake for a literal representation of the real thing.

Everything about "A Clockwork Orange" is carefully designed to make this difference apparent, at least to the adult viewer, but there may be a very real problem when even such stylized representations are seen by immature audiences. That, however, is another subject entirely, and one for qualified psychiatrists to ponder. In my opinion Kubrick has made a movie that exploits only the mystery and variety of human conduct. And because it refuses to use the emotions conventionally, demanding instead that we keep a constant, intellectual grip on things, it's a most unusual--and disorienting--movie experience.

CLICK HERE TO GET A PRE-MADE MYSPACE LAYOUT