DOWNLOAD "PURE & TRUE RUBAB" AT iTUNES TODAY!

HEAR QURAISHI PLAYING IN "THE KITE RUNNER"

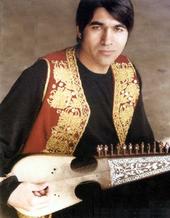

THE ARTIST, QURAISHI

Quraishi’s earliest influences and family lineage include musicians and instrument makers. His father made him his first rubab as a young man. While growing up in Kabul, the self-taught artist became quickly well-versed in the folk styles and regional genres of the numerous ethnic groups found throughout Afghanistan, including the Pashtu, Uzbek, Tajik, and others. Quraishi also steeped himself in the discipline and formalistic principals of classical Hindustani music theory that constitutes the foundation of Afghanistan’s art music. Technically, Quraishi possesses a masterful sense of rhythm and an acute ear. But it is his poetic heart that moves his listeners with his sensitive interpretations of the classical repertoire infused with his fresh and youthful expressions on his original compositions.

THE INSTRUMENT, RUBAB

The rubab, an ancient instrument with a skin face belonging to the short neck lute family, is the national instrument of Afghanistan. It is traditionally mad with a single piece of mulberry wood, which is mystically associated with the silkworm. There are typically three melody strings (now most often made of gut or nylon) and as many as twenty sympathetic strings that are variably tuned to the modes or ragas. These sympathetic strings impart a deep resonance and unique timbre to the rubab. The instrument is often richly ornamented with inlay of bone and ivory, and occasionally encrusted with lapis lazuli, mother of pearl, or other modern materials.

THE DRUMMER, CHATRAM SHANI

Chatram Sahni is a drummer par excellence, having served his apprenticeship playing on Afghan radio in the 70’s. A favorite accompanist for all the famous Afghan singers, Chatram knows all the traditional Afghan rhythms.

THE INSTRUMENT, DHOL

The dhol, the double-headed, typical Afghani drum, is usually made from mulberry wood with goat skin stretched over both ends and is tunable with a series of adjustable ropes. These days there are fewer and fewer examples of this ancient instrument to be found.

PURE AND TRUE RUBAB

As the world music scene explodes, the music of Afghanistan has been conspicuously absent - until now. Twenty years of war and the Taliban’s systematic repression of instrumental music have taken its toll. With a little searching, one can find historical field recordings from thirty years ago, or current synthesizer pop music made in the Afghan diaspora, but the vitality and immediacy of traditional artists making music for our times is largely missing. Quraishi’s sensitive interpretations form a living and vital link between the rich tradition of the Afghan classical court music, the golden years of Afghan radio, the musical realities of today’s diverse immigrant communities, and the future of a nation’s musical identity. It is astonishing how just two musicians engaged in a musical conversation can coax so much sound and feeling and so many variations from such simple instruments. No electronic effects here, just virtuosity.

Afghan music is unique in its richness, range, and variety, evoking a strong sense of place. Strategically situated at the center of the ancient Silk Road, the land can be heard in the intricacies of the music—one senses the vastness of wild mountains in the rhythms, as well as the loneliness of the desert in the melodies. Certainly, the influence of the Indian subcontinent can be heard in the ragas and instrumentation, but the simple and haunting strains of China and the Far East are also evident in the use of pentatonic scales. The Central Asian shashmaquam from Samarakhan can also be made out in certain Uzbek and Tajik tunes, or the ornamentation typical of the Persian Radif as found in the music from the western part of the country, especially the city of Herat. But if one listens closely, there is also the hint of something more—the minor scales of the Middle East and the intricate melodies that intertwine like Greek rebetika, recalling the playfulness and invention of Celtic music, the soulfulness of the American blues, or the improvisations of modern jazz.

At times, the rocking back beat will make you want to dance. Ecstatic states are often the result of the musicians steadily increasing the tempo—that is, until they decide to have a little fun by stopping in mid-song as they would in Loggari-style music. At other times, meditative contemplation is the order. With a depth of feeling, call and response phrases are repeated between musicians, creating the hypnotic, mesmerizing trance-like quality of a Sufi Zikar, connecting the music back to its roots in mystical Sufi poets and the ghazals they wrote. Rumi—though most often associated with the whirling dervishes of Turkey—was, after all, originally from Afghanistan.

TRACK LISTING:

1. Herati (Folk)

2. Valley (Folk)

3. Meg (Quraishi)

4. Badakshi (Folk)

5. Qalin (Folk)

6. Hope (Quraishi)

7. Jani-ba-Lab (Folk)

8. Ashoqi (Khial)

(QURAISHI PLAYING IN BACKGROUND MUSIC)