Extracts from Justus Collins Castleman (1905):

A SHORT LIFE OF ARNOLD

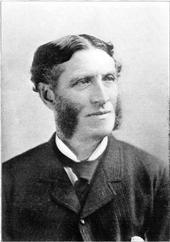

Matthew Arnold, poet and critic, was born in the village of Laleham, Middlesex County, England, December 24, 1822. He was the son of Dr. Thomas Arnold, best remembered as the great Head Master at Rugby and in later years distinguished also as a historian of Rome, and of Mary Penrose Arnold, a woman of remarkable character and intellect.

Devoid of stirring incident, and, on the whole, free from the eccentricities so common to men of genius, the story of Arnold's life is soon told. As a boy he lived the life of the normal English lad, with its healthy routine of task and play. He was at school at both Laleham and Winchester, then at Rugby, where he attracted attention as a student and won a prize for poetry. In 1840 he was elected to an open scholarship at Balliol College, Oxford, and the next year matriculated for his university work. Arnold's career at Oxford was a memorable one. Having taken the Newdigate prize for English verse, and also having won a scholarship, he was graduated with honors in 1844, and in March of the following year had the additional distinction of being elected a Fellow of Oriel, the crowning glory of an Oxford graduate. He afterward taught classics for a short time at Rugby, then in 1847 accepted the post of private secretary to the Marquis of Lansdowne, Lord President of the Council, which position he occupied until 1851, when he was appointed Lay Inspector of Schools by the Committee on Education. The same year he married Frances Lucy Wightman, daughter of Sir William Wightman, judge of the Court of the Queen's Bench. Together they had six children. He resigned his position under the Committee of Council on Education, in 1886.

In the meantime Arnold's pen had not been idle. His first volume of verse, "The Strayed Reveller and Other Poems", appeared (1848), and although quietly received, slowly won its way into public favor. The next year the narrative poem, "The Sick King in Bokhara", came out, and was followed in turn by a third volume in 1853, under the title of "Empedocles on Etna and Other Poems". By this time Arnold's reputation as a poet was established, and in 1857 he was elected Professor of Poetry at Oxford, where he began his career as a lecturer, in which capacity he twice visited America. "Merope, a Tragedy" (1856) and a volume under the title of "New Poems" (1869) finish the list of his poetical works, with the exception of occasional verses.

Arnold's prose works, aside from his letters, consist wholly of critical essays, in which he has dealt fearlessly with the greater issues of his day. He won respect and reputation while he lived, and his works continue to attract men's minds, although with much unevenness. It has been said of him that, of all the modern poets, except Goethe, he was the best critic, and of all the modern critics, with the same exception, he was the best poet. He died at Liverpool, where he had gone to meet his daughter returning from America, April 15, 1888. By his death the world lost an acute and cultured critic, a refined writer, an earnest educational reformer, and a noble man. He was buried in his native town, Laleham.

Oriel Cottage, Oxford

ARNOLD THE POET

Matthew Arnold was essentially a man of the intellect. No other author of modern times, perhaps no other English author of any time, appeals so directly as he to the educated classes. Even a cursory reading of his pages, prose or verse, reveals the scholar and the critic. He is always thinking, always brilliant, never lacks for a word or phrase; and on the whole, his judgments are good. Between his prose and verse, however, there is a marked difference, both in tone and spiritual quality. True, each possesses the note of a lofty, though stoical courage; reveals the same grace of finish and exactness of phrase and manner; and is, in equal degree, the output of a singularly sane and noble nature; but here the comparison ends; for, while his prose is often stormy and contentious, his poetry has always about it an atmosphere of entire repose. The cause of this difference is not far to seek. His poetry, written in early manhood, reflects his inner self, the more lovable side of his nature; while his prose presents the critic and the reformer, pointing out the good and bad, and permitting at times a spirit of bitterness to creep in, as he endeavors to arouse men out of their easy contentment with themselves and their surroundings.

Although his poetic life was brief, it was of a very high order, his poems ranking well up among the literary productions of the last century. As a popular poet, however, he will probably never class with Tennyson or Longfellow. His poems are too coldly classical and too unattractive in subject to appeal to the casual reader, who is, generally speaking, inclined toward poetry of the emotions rather than of the intellect--Arnold's usual kind. That he recognized this himself, witness the following quiet statements made in letters to his friends: "My poems are making their way, I think, though slowly, and are perhaps never to make way very far. There must always be some people, however, to whom the literalness and sincerity of them has a charm.... They represent, on the whole, the main movement of mind of the last quarter of a century, and thus they will probably have their day, as people become conscious to themselves of what that movement of mind is, and interested in the literary productions which reflect it." Time has verified the accuracy of this judgment. In short, Arnold has made a profound rather than a wide impression. To a few, however, of each generation, he will continue to be a "voice oracular,"--a poet with a purpose and a message.

Obviously, the sources of Arnold's poetic culture were classical. As one critic has tersely said, "He turned over his Greek models by day and by night." Here he found his ideal standards, and here he brought for comparison all questions that engrossed his thoughts. Homer (he replied to an inquirer) and Epictetus (of mood congenial with his own) were props of his mind, as were Sophocles, "who saw life steadily and saw it whole," and Marcus Aurelius, whom he called the purest of men. These like natures afforded him repose and consolation. Greek epic and dramatic poetry and Greek philosophy appealed profoundly to him. d the thinking power; have so well satisfied the religious sense." More than any other English poet he prized the qualities of measure, proportion, and restraint; and to him lucidity, austerity, and high seriousness, conspicuous elements of classic verse, were the substance of true poetry.

Pains Hill Cottage, Cobham, Surrey. Arnold lived here from 1873 until his death in 1888.

ARNOLD THE CRITIC

The following extract on Arnold as a critic are quoted from a well-known authority.

"Arnold's prose has little trace of the wistful melancholy of his verse. It is almost always urbane, vivacious, light-hearted. The classical bent of his mind shows itself here, unmixed with the inheritance of romantic feeling which colors his poetry. Not only is his prose classical in quality, by virtue of its restraint, of its definite aim, and of the dry white light of intellect which suffuses it; but the doctrine which he spent his life in preaching is based upon a classical ideal, the ideal of symmetry, wholeness, or, as he daringly called it, "perfection".... Wherever, in religion, politics, education, or literature, he saw his countrymen under the domination of narrow ideals, he came speaking the mystic word of deliverance, 'Culture.' Culture, acquaintance with the best which has been thought and done in the world, is his panacea for all ills.... In almost all of his prose writing he attacks some form of 'Philistinism,' by which word he characterized the narrow-mindedness and self-satisfaction of the British middle class.

Matthew Arnold's grave at Laleham Churchyard, where he is buried with his wife and three sons.