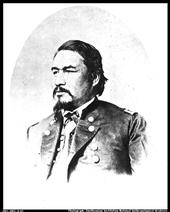

Do-ne-ho-ga-wa wearing the medal given to his ancestor, the great Seneca orator Red Jacket

Â

Ely S. Parker

Do-ne-ho-ga-wa

Ely Samuel Parker (1828 – August 31, 1895), (born Hasanoanda, later known as Donehogawa) was an Iroquois of the Seneca tribe born at Indian Falls, New York (then part of the Tonawanda Reservation). During the American Civil War, he wrote the final draft of the Confederate surrender terms at Appomattox and rose to the rank of Brigadier General.

Although Ely Parker is best known for his role in drafting the terms of surrender that ended the Civil War, his life's work was far greater than that single act. This "one real American," as General Lee referred to him, was born destined for greatness, or so it had been prophesied. In 1828, four months before his birth at the Tonawanda Seneca reservation in Indian Falls, N.Y., Parker's mother had an unsettling dream in which she beheld a broken rainbow reaching from the home of Indian agent Erastus Granger, in Buffalo, to the reservation. Troubled, Elizabeth Johnson Parker (known to her people as Gaontguttwus) visited a Seneca dream interpreter in an attempt to better understand what she had seen. His translation of her vision was nothing less than spectacular. The dream interpreter told Parker: "A son will be born to you who will be distinguished among his nation as a peacemaker; he will become a white man as well as an Indian, with great learning; he will be a warrior for the palefaces; he will be a wise white man, but will never desert his Indian people or 'lay down his horns as a great Iroquois chief'; his name will reach from the East to the West--the North to the South, as great among his Indian family and the palefaces. His sun will rise on Indian land and set on the white man's land. Yet the land of his ancestors will fold him in death."

As one of the six nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, the Seneca participated in a tradition of sending the flower of their youth to learn at schools in the United States. Young Ha-sa-no-an-da Parker excelled in his early schooling, but refused to learn English. He did choose the Anglicized Ely as a first name for himself through his interactions with the Reverend Ely Stone. Ely Parker soon realized that in order to function properly in both worlds, a mastery of the English language would be necessary. In 1842, Ely entered Yates Academy, in New York. There he quickly mastered the English language in both its spoken and written forms, and became noted for his oratorical abilities. His stay at Yates Academy was a busy one: He had an active social life, and at various times was called upon by his tribal elders to represent the reservation in Washington regarding several treaty disputes with the United States government. Involved in these disputes from the age of 15, Parker acquitted himself well against a variety of miscreants who were attempting to use two illicit treaties, signed by puppet chiefs in 1838 and 1842, to take the Senecas' lands. He so impressed Washington society that he was invited to dine with President and Mrs. James K. Polk at the White House when he was only 18 years old.

Parker matriculated in the prestigious Cayuga Academy in Aurora, Ontario. His stay was mostly a pleasant one; again he was socially active and became involved in the school's debate club, which stimulated his interest in the law. An attempt to get into Harvard in 1847 failed. Undeterred, Parker became a law student under district attorney and Indian subagent William P. Angel in Ellicottville, N.Y. Parker's career as a lawyer was unfor- tunately curtailed when his patron fell out of favor with the ruling Democratic Party; shortly thereafter, Parker was declared ineligible for the bar because he was not an American citizen. But despite being shunned by the legal community, Parker did find a place in society where he was welcome throughout his life. In 1847, Parker became a member of the Batavia Lodge Number 88, and remained a Mason until the day he died.

Following his thwarted attempts to practice law, Parker elected instead to become an engineer. He may have briefly attended Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, acquiring an education in civil engineering; however, the school has no record of his attendance, and the story may be apocryphal. Whatever the case, in 1849 Parker accepted an engineering position on the nearby Genesee River. He began as second assistant engineer in a project to extend the Genesee Valley Canal toward the Allegheny River; in 1851 he was promoted to first assistant engineer, a position he would hold for four years. During this time, he also worked on improvements to the Erie Canal.

Also in 1851, the Iroquois bestowed upon Parker their greatest honor in recognition of his tireless service: He became Grand Sachem of the Six Nations, and was asked to serve as mentor and intermediary for his people. With this title the 23-year-old also acquired the sacred name of Donehogawa, Keeper of the Western Door of the Iroquois Longhouse. In 1853, the governor of New York formally recognized Parker as the chief representative of the Iroquois confederacy, and the state government treated him as the head chief in any dealings with the confederacy.

Near the start of the Civil War, Parker went to Albany and offered to raise a volunteer regiment of Iroquois to fight for the Union. He was flatly refused; the governor made it clear that Indians were not wanted in the New York Volunteers. Later, Parker offered his services to the Federal government as an engineer; again he was rebuffed. Secretary of State William Seward put it to him bluntly: "The fight must be settled by the white men alone. Go home, cultivate your farm, and we will settle our troubles without any Indian aid." Dispirited, Parker returned home, where for two years he tended his crops, busied himself in Masonic and Seneca activities, and worked behind the scenes to obtain a commission in the Union Army.

In 1863, after slicing through miles of red tape, engineer-hungry Grant fulfilled Parker's wish, and Parker was breveted as a captain of engineers in the U.S. Army. Although according to Iroquois custom no Grand Sachem could go to war and retain his tribal title, a special dispensation was made for the honored Donehogawa, as this was not a war against another tribe, but between white men.

Beginning as an assistant adjutant general in Brig. Gen. J.E. Smith's division at Vicksburg, Miss., Parker quickly worked his way up the ladder, proving himself as capable at directing volunteer soldiers as he had been at engineering, public speaking and lobbying for his people. He served with distinction at Grant's side at Vicksburg, and by mid-1864 had been placed on Grant's personal staff, where he served as the commander's de facto personal military secretary. This position was made official in August 1864, when Parker replaced Lt. Col. William Rowley, a longtime colleague of General Grant's who was forced to retire due to ill health. The promotion brought with it the rank of lieutenant colonel, which, in the view of New York Herald correspondent Sylvanus Cadwallader, was merely "a partial reward for invaluable services."

Parker's selection to draft the surrender papers at Appomattox was a just recognition of his exquisite penmanship and skill with the English language. The drafting of the articles of surrender, literally Parker's last act in the war, was unquestionably the crowning moment of his military career, and one of the highlights of his life as well. Certainly it provided him with much currency (social and otherwise) later in life. However, the U.S. military wasn't finished with Parker, or he with it. He stayed on as a member of Grant's staff until 1869, eventually rising to the rank of brigadier general.

The presidential election of 1868 brought an abrupt change in Parker's career. In November of that year, Civil War hero Lt. Gen. Grant became President-elect Grant, and he soon brought his friends with him into the White House. Parker was appointed commissioner of Indian Affairs, based on his previous experience and on the assumption that no one was better qualified to helm the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). Thus Parker became the first Indian to hold the office. On April 26, 1869, after being confirmed by Congress, Parker resigned his Army commission and took his place as head of the BIA. His two-year reign was a tempestuous one; he was too honest, too interested in the cause of justice for his own race, for it to be otherwise.

After he left government service, Parker moved to Wall Street and proceeded to make a fortune on the stock market; he lost it just as quickly in the market troubles of 1873Â-1875. Thereafter, he made an attempt to re-enter the profession of civil engineering, but found to his dismay that it had "run away from him" during his absence. In 1876, he was forced to take a low-paying job as a clerk in the New York City police department. But Parker still managed to stay active in the militia, various military societies and the Masons, achieving high rank within each organization. Likewise, he and his wife were well respected in New York social circles.

Plagued by strokes and diabetes in his last years, Parker died on August 30, 1895, at his country house in Fairfield, Conn. He was buried with full military honors and much fanfare at Oak Lawn Cemetery in Fairfield. In 1897, he was reinterred next to the remains of his famous ancestor, the Seneca orator Red Jacket, at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo, N.Y. This cemetery, which was located much closer to the Tonawanda Reservation, had once been part of the old Granger farm--ultimately fulfilling his mother's prophetic dream. After successfully carving niches for himself in two dissimilar worlds, Grand Sachem General Ely Parker was at last laid to rest within the comforting bosom of his ancestral homeland.

Â

Â

Try the BEST MySpace Editor and MySpace Backgrounds at MySpace Toolbox !