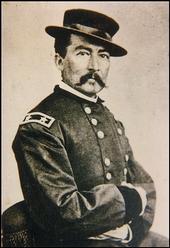

Little Phil Sheridan

Sheridan was born in Albany, New York, the son of John and Mary Meenagh Sheridan, immigrants from the parish of Killinkere, County Cavan, Ireland, and grew up in Somerset, Ohio. Fully grown, he reached only 5 feet 5 inches tall, a stature that led to the nickname, "Little Phil." Abraham Lincoln described his appearance in a famous anecdote: "A brown, chunky little chap, with a long body, short legs, not enough neck to hang him, and such long arms that if his ankles itch he can scratch them without stooping."

In 1848, he obtained an appointment to the United States Military Academy from Congressman Thomas Ritchey. In his third year at West Point, Sheridan was suspended for a year for fighting with a classmate, William R. Terrill. The previous day, Sheridan had threatened to run him through with a bayonet in reaction to a perceived insult on the parade ground. He graduated in 1853, 34th in his class of 52 cadets.

Sheridan was commissioned as a brevet second lieutenant and was assigned to the 1st U.S. Infantry regiment at Fort Duncan, Texas, then to the 4th U.S. Infantry at Fort Reading, California. He became involved with the Yakima War and Rogue River Wars, gaining experience in leading small combat teams, being wounded (a bullet grazed his nose on March 28, 1857) and some of the diplomatic skills needed for negotiating with Indian tribes. He was promoted to first lieutenant in March 1861, just before the Civil War, and to captain in May, immediately after Fort Sumter.

In December of 1861, Sheridan was appointed chief commissary officer of the Army of Southwest Missouri, but convinced the department commander, Halleck, to give him the position of quartermaster general as well. In January 1862, he reported for duty to Maj. Gen. Samuel Curtis and served under him at the Battle of Pea Ridge before being replaced in his staff position by an associate of Curtis's. Returning to Halleck's headquarters, he accompanied the army on the Siege of Corinth and served as an assistant to the department's topographical engineer, but also made the acquaintance of Brig. Gen. William T. Sherman, who offered him the colonelcy of an Ohio infantry regiment. This appointment fell through, but Sheridan was subsequently aided by friends (including future Secretary of War Russell A. Alger), who petitioned Michigan Governor Austin Blair on his behalf. Sheridan was appointed colonel of the 2nd Michigan Cavalry on May 27, 1862, despite having no experience in the mounted arm.

A month later, Sheridan commanded his first forces in combat, leading a small brigade that included his regiment. At the Battle of Boonville, July 1, 1862, he held back several regiments of Brig. Gen. James R. Chalmers's Confederate cavalry, deflected a large flanking attack with a noisy diversion, and reported critical intelligence about enemy dispositions. His actions so impressed the division commanders, including Brig. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, that they recommended Sheridan's promotion to brigadier general. They wrote to Halleck, "Brigadiers scarce; good ones scarce. ... The undersigned respectfully beg that you will obtain the promotion of Sheridan. He is worth his weight in gold." The promotion was approved in September, but dated effective July 1 as a reward for his actions at Boonville. It was just after Boonville that one of his fellow officers gave him the horse that he named Rienzi (after the skirmish of Rienzi, Mississippi), which he would ride throughout the war.

Sheridan was assigned to command the 11th Division, III Corps, in Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell's Army of the Ohio. On October 8, 1862, Sheridan led his division in the Battle of Perryville. Ordered not to provoke a general engagement until the full army was present, Sheridan nevertheless pushed his men far beyond the Union battle line, to occupy the contested water supply at Doctor's Creek. Although he was ordered back by III Corps commander, Maj. Gen. Charles Gilbert, the Confederates were incited by Sheridan's rash movement to open the battle, a bloody stalemate in which both sides suffered heavy casualties.

On December 31, 1862, the first day of the Battle of Stones River, Sheridan anticipated a Confederate assault and positioned his division in preparation for it. His division held back the Confederate onslaught on his front until their ammunition ran out and they were forced to withdraw. This action was instrumental in giving the Union army time to rally at a strong defensive position. For his actions, he was promoted to major general on April 10, 1863 (with date of rank December 31, 1862) and given command of the 2nd Division, IV Corps, Army of the Cumberland. In six months, he had risen from captain to major general.

The Army of the Cumberland recovered from the shock of Stones River and prepared for its summer offensive against Confederate General Braxton Bragg. Sheridan's was the lead division advancing against Bragg in Rosecrans's brilliant Tullahoma Campaign. On the second day of the Battle of Chickamauga, September 20, 1863, Sheridan's division made a gallant stand on Lytle Hill against an attack by the Confederate corps of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, but was overwhelmed. Army commander Rosecrans fled to Chattanooga without leaving orders for his subordinates, and Sheridan, unsure what to do, ordered his division to retreat with the rest of the army. Only Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas's division stood fast. Receiving a message from Thomas about the desperate stand his men were making alone on the battlefield, Sheridan ordered his division back to the fighting, but they took a circuitous route and did not arrive before the Union army was defeated. Nevertheless, Sheridan's attempt to return probably saved his career, unlike those of Rosecrans and some of Sheridan's peers.

During the Battle of Chattanooga, at Missionary Ridge on November 25, 1863, Sheridan's division and others in George Thomas's army broke through the Confederate lines in a wild charge that exceeded the orders and expectations of Thomas and Ulysses S. Grant. Just before his men stepped off, Sheridan told them, "Remember Chickamauga," and many shouted its name as they advanced as ordered to a line of rifle pits in their front. Faced with enemy fire from above, however, they continued up the ridge. Sheridan spotted a group of Confederate officers outlined against the crest of the ridge and shouted, "Here's at you!" An exploding shell sprayed him with dirt and he responded, "That's damn ungenerous! I shall take those guns for that!" The Union charge broke through the Confederate lines on the ridge and Bragg's army fell into retreat. Sheridan impulsively ordered his men to pursue Bragg to the Confederate supply depot at Chickamauga Station, but called them back when he realized that his was the only command so far forward. General Grant reported after the battle, "To Sheridan's prompt movement, the Army of the Cumberland and the nation are indebted for the bulk of the capture of prisoners, artillery, and small arms that day. Except for his prompt pursuit, so much in this way would not have been accomplished.

Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, newly promoted to be general-in-chief of all the Union armies, summoned Sheridan to the Eastern Theater to command the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac. Sheridan arrived at the headquarters of the Army of the Potomac on April 5, 1864, less than a month before the start of Grant's massive Overland Campaign against Robert E. Lee.

In the early battles of the campaign, Sheridan's cavalry was relegated by army commander Maj. Gen. George G. Meade to its traditional role—screening, reconnaissance, and guarding trains and rear areas—much to Sheridan's frustration. In the Battle of the Wilderness the dense forested terrain prevented any significant cavalry role. Sheridan's troopers failed to clear the road from the Wilderness, losing engagements along the Plank Road on May 5 and Todd's Tavern on May 6 through May 8, allowing the Confederates to seize the critical crossroads before the Union infantry could arrive.

When Meade reprimanded Sheridan for not performing his duties of screening and reconnaissance as ordered, Sheridan went directly to Meade's superior, General Grant, recommending that his corps be assigned to strategic raiding missions. Grant agreed, and from May 9 through May 24, sent him on a raid toward Richmond, directly challenging the Confederate cavalry. The raid was less successful than hoped; although his soldiers managed to kill Confederate cavalry commander Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart at Yellow Tavern on May 11, the raid never seriously threatened Richmond and it left Grant without cavalry intelligence for Spotsylvania and North Anna.

Throughout the war, the Confederacy sent armies out of Virginia through the Shenandoah Valley to invade Maryland and Pennsylvania and threaten Washington, D.C. Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early, following the same pattern in the Valley Campaigns of 1864, and hoping to distract Grant from the Siege of Petersburg, attacked Union forces near Washington and raided several towns in Pennsylvania. Grant, reacting to the political commotion caused by the invasion, organized the Middle Military Division, whose field troops were known as the Army of the Shenandoah, and appointed Sheridan to command it. His mission was not only to defeat Early's army and to close off the Northern invasion route, but to deny the Shenandoah Valley as a productive agricultural region to the Confederacy. Grant told Sheridan, "The people should be informed that so long as an army can subsist among them recurrences of these raids must be expected, and we are determined to stop them at all hazards. ... Give the enemy no rest ... Do all the damage to railroads and crops you can. Carry off stock of all descriptions, and negroes, so as to prevent further planting. If the war is to last another year, we want the Shenandoah Valley to remain a barren waste."

On September 19, Sheridan beat Early's much smaller army at Third Winchester and followed up on September 22 with a victory at Fisher's Hill. As Early attempted to regroup, Sheridan began the punitive operations of his mission, sending his cavalry as far south as Waynesboro to seize or destroy livestock and provisions, and to burn barns, mills, factories, and railroads. Sheridan's men did their work relentlessly and thoroughly, rendering over 400 mi.² uninhabitable. The destruction presaged the scorched earth tactics of Sherman's March to the Sea through Georgia—deny an army a base from which to operate and bring the effects of war home to the population supporting it. The residents referred to this widespread destruction as "The Burning."

Although Sheridan assumed that Jubal Early was effectively out of action and he considered withdrawing his army to rejoin Grant at Petersburg, Early received reinforcements and, on October 19 at Cedar Creek, launched a well-executed surprise attack while Sheridan was absent from his army, ten miles away at Winchester. Hearing the distant sounds of artillery, he rode aggressively to his command. He reached the battlefield about 10:30 a.m. and began to rally his men. Fortunately for Sheridan, Early's men were too occupied to take notice; they were hungry and exhausted and fell out to pillage the Union camps. Sheridan's actions are generally credited with saving the day. Early had been dealt his most significant defeat, rendering his army almost incapable of future offensive action. Sheridan received a personal letter of thanks from Abraham Lincoln and a promotion to major general in the regular army as of November 8, 1864, making him the fourth ranking general in the Army, after Grant, Sherman, and Meade.

In March 1865, Sheridan moved to rejoin the Army of the Potomac at Petersburg. He wrote in his memoirs, "Feeling that the war was nearing its end, I desired my cavalry to be in at the death." His finest service of the Civil War was demonstrated during his relentless pursuit of Robert E. Lee's Army, effectively managing the most crucial aspects of the Appomattox Campaign for Grant. On the way to Petersburg, at the Battle of Waynesboro, March 2, he trapped the remainder of Early's army and 1,500 soldiers surrendered. On April 1, he cut off Gen. Lee's lines of support at Five Forks, forcing Lee to evacuate Petersburg.

Sheridan's aggressive and well-executed performance at the Battle of Sayler's Creek on April 6 effectively sealed the fate of Lee's army, capturing over 20% of his remaining men. President Lincoln sent Grant a telegram on April 7: "Gen. Sheridan says 'If the thing is pressed I think that Lee will surrender.' Let the thing be pressed." At Appomattox Court House, April 9, 1865, Sheridan blocked Lee's escape, forcing the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia later that day. Grant summed up Little Phil's performance in these final days: "I believe General Sheridan has no superior as a general, either living or dead, and perhaps not an equal".

After the war,Sheridan was appointed by Grant to head the Department of the Missouri and pacify the Plains Indians. His troops, even supplemented with state militia, were spread too thin to have any real effect. He conceived a strategy similar to the one he used in the Shenandoah Valley. In the Winter Campaign of 1868–69 he attacked the Cheyenne, Kiowa, and Comanche tribes in their winter quarters, taking their supplies and livestock and killing those who resisted, driving the rest back into their reservations. By promoting in Congressional testimony the slaughter of the vast herds of American bison on the Great Plains and by other means, Sheridan helped deprive the Indians of their primary source of food. This strategy continued until the Indians honored their treaties. Sheridan's department conducted the Red River War, the Ute War, and the Black Hills War, which resulted in the death of a trusted subordinate, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer. The Indian raids subsided during the 1870s and were almost over by the early 1880s, as Sheridan became the commanding general of the U.S. Army.

In 1871, Sheridan was present in Chicago during the Great Chicago Fire and coordinated military relief efforts. The mayor, to calm the panic, placed the city under martial law, and issued a proclamation putting Sheridan in charge. As there were no widespread disturbances, martial law was lifted within a few days. Although Sheridan's personal residence was spared, all of his professional and personal papers were destroyed.

Sheridan was promoted to lieutenant general on March 4, 1869. In 1870, President Grant sent him to observe and report on the Franco-Prussian War. As a guest of the King of Prussia, he was present when Napoleon III surrendered to the Germans.

On November 1, 1883, Sheridan succeeded William T. Sherman as Commanding General, U.S. Army, and held that position until shortly before his death. In 1888, he suffered a series of massive heart attacks two months after sending his memoirs to the publisher. After his first heart attack, the U.S. Congress quickly passed legislation to promote him to general (the rank was titled "General of the Army of the United States", by Act of Congress June 1, 1888, the same rank achieved earlier by Grant and Sherman, which is equivalent to a four-star general, O-10, in the modern U.S. Army) and he received the news from a congressional delegation with joy, despite his pain. His family moved him from the heat of Washington and he died in his vacation cottage at Nonquitt, Massachusetts. His body was returned to Washington and he was buried on a hillside facing the capital city near Arlington House in Arlington National Cemetery. His wife Irene never remarried, saying, "I would rather be the widow of Phil Sheridan than the wife of any man living."

Try the BEST MySpace Editor and MySpace Backgrounds at MySpace Toolbox !