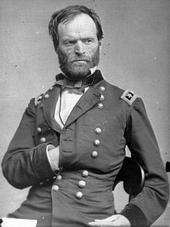

William Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman (February 8, 1820 – February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator and author. He served as a General in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–65), for which he received recognition for his outstanding command of military strategy as well as criticism for the harshness of the "scorched earth" policies that he implemented in conducting total war against the Confederate States. Military historian Basil Liddell Hart famously declared that Sherman was "the first modern general".

Sherman served under General Ulysses S. Grant in 1862 and 1863 during the campaigns that led to the fall of the Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg on the Mississippi River and culminated with the routing of the Confederate armies in the state of Tennessee. In 1864, Sherman succeeded Grant as the Union commander in the western theater of the war. He proceeded to lead his troops to the capture of the city of Atlanta, a military success that contributed to the re-election of President Abraham Lincoln. Sherman's subsequent march through Georgia and the Carolinas further undermined the Confederacy's ability to continue fighting. He accepted the surrender of all the Confederate armies in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida in April 1865.

When Grant became president, Sherman succeeded him as Commanding General of the Army (1869–83). As such, he was responsible for the conduct of the Indian Wars in the western United States. He steadfastly refused to be drawn into politics and in 1875 published his Memoirs, one of the best-known firsthand accounts of the Civil War.

Early life

Sherman was born in 1820 in Lancaster, Ohio, near the shores of the Hocking River. His father Charles Robert Sherman, a successful lawyer who sat on the Ohio Supreme Court, died unexpectedly in 1829. He left his widow, Mary Hoyt Sherman, with eleven children and no inheritance. Following this tragedy, the nine-year-old Sherman was raised by a Lancaster neighbor and family friend, attorney Thomas Ewing, a prominent member of the Whig Party who served as senator from Ohio and as the first Secretary of the Interior. Sherman was distantly related to the politically influential Baldwin, Hoar & Sherman family and grew to admire American founding father Roger Sherman.

Senator John Sherman

Sherman's older brother Charles Taylor Sherman became a federal judge. One of his younger brothers, John Sherman, served as a U.S. senator and Cabinet secretary. Another younger brother, Hoyt Sherman, was a successful banker. Two of his foster brothers served as major generals in the Union Army during the Civil War: Hugh Boyle Ewing, later an ambassador and author, and Thomas Ewing, Jr., who would serve as defense attorney in the military trials against the Lincoln conspirators.

Military training and service

Senator Ewing secured an appointment for the 16-year-old Sherman as a cadet in the United States Military Academy at West Point, where he roomed and became good friends with another important future Civil War General, George H. Thomas. There Sherman excelled academically, but he treated the demerit system with indifference. Fellow cadet William Rosecrans would later remember Sherman at West Point as "one of the brightest and most popular fellows," and "a bright-eyed, red-headed fellow, who was always prepared for a lark of any kind."

Upon graduation in 1840, Sherman entered the Army as a second lieutenant in the 3rd U.S. Artillery and saw action in Florida in the Second Seminole War against the Seminole tribe. He was later stationed in Georgia and South Carolina. As the foster son of a prominent Whig politician, in Charleston, the popular Lt. Sherman moved within the upper circles of Old South society.

Edward Ord

While many of his colleagues saw action in the Mexican-American War, Sherman performed administrative duties in the captured territory of California. He and fellow officer Lieutenant Edward Ord reached the town of Yerba Buena two days before its name was changed to San Francisco. In 1848, Sherman accompanied the military governor of California, Col. Richard Barnes Mason, in the inspection that officially confirmed the claim that gold had been discovered in the region, thus inaugurating the California Gold Rush. Sherman, along with the above-mentioned Edward Ord, assisted in surveys for the sub-divisions of the town that would become Sacramento.

Colonel Richard Barnes Mason

Sherman earned a brevet promotion to captain for his "meritorious service", but his lack of a combat assignment discouraged him and may have contributed to his decision to resign his commission. Sherman would become one of the relatively few high-ranking officers in the Civil War who had not fought in Mexico.

Eleanor Boyle Ewing Sherman

Marriage and business career

In 1850, Sherman was promoted to the substantive rank of Captain and married Thomas Ewing's daughter, Eleanor Boyle ("Ellen") Ewing, in a Washington ceremony attended by President Zachary Taylor and other political luminaries. (Thomas Ewing was serving as the first Secretary of the Interior at the time.) Like her mother, Ellen Ewing Sherman was a devout Roman Catholic, and the Sherman’s eight children were reared in that faith.

In 1853, Sherman resigned his Captaincy and became manager of the San Francisco branch of a St. Louis based bank. He returned to San Francisco at a time of great turmoil in the West. He survived two shipwrecks and floated through the Golden Gate on the overturned hull of a foundering lumber schooner. Sherman suffered from stress-related asthma because of the city's brutal financial climate. Late in life, regarding his time in real-estate-speculation-mad San Francisco, Sherman recalled: "I can handle a hundred thousand men in battle, and take the City of the Sun, but am afraid to manage a lot in the swamp of San Francisco." In 1856, during the vigilante period, he served briefly as a major general of the California militia.

Sherman's San Francisco branch closed in May 1857, and he relocated to New York on behalf of the same bank. When the bank failed during the financial Panic of 1857, he turned to the practice of law in Leavenworth, Kansas, at which he was also unsuccessful.

Military college superintendent

In 1859, Sherman accepted a job as the first superintendent of the Louisiana State Seminary of Learning & Military Academy in Pineville, Louisiana, a position he sought at the suggestion of Major D. C. Buell and secured due to General G. Mason Graham. He proved an effective and popular leader of that institution, which would later become Louisiana State University (LSU). Colonel Joseph P. Taylor, the brother of the late President Zachary Taylor, declared that "if you had hunted the whole army, from one end of it to the other, you could not have found a man in it more admirably suited for the position in every respect than Sherman."

On hearing of South Carolina's secession from the United States, Sherman observed to a close friend, Professor David F. Boyd of Virginia, an enthusiastic secessionist, almost perfectly describing the four years of war to come:

“You people of the South don't know what you are doing. This country will be drenched in blood, and God only knows how it will end. It is all folly, madness, a crime against civilization! You people speak so lightly of war; you don't know what you're talking about. War is a terrible thing! You mistake, too, the people of the North. They are a peaceable people but an earnest people, and they will fight, too. They are not going to let this country be destroyed without a mighty effort to save it… Besides, where are your men and appliances of war to contend against them? The North can make a steam engine, locomotive, or railway car; hardly a yard of cloth or pair of shoes can you make. You are rushing into war with one of the most powerful, ingeniously mechanical, and determined people on Earth—right at your doors. You are bound to fail. Only in your spirit and determination are you prepared for war. In all else you are totally unprepared, with a bad cause to start with. At first you will make headway, but as your limited resources begin to fail, shut out from the markets of Europe as you will be, your cause will begin to wane. If your people will but stop and think, they must see in the end that you will surely fail.â€

In January 1861 just before the outbreak of the Civil War, Sherman was required to accept receipt of arms surrendered to the State Militia by the U.S. Arsenal at Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Instead of complying, he resigned his position as superintendent and returned to the North, declaring to the governor of Louisiana, "On no earthly account will I do any act or think any thought hostile ... to the ... United States."

After the war, General Sherman donated two cannons to the institution. These cannons had been captured from Confederate forces and had been used to start the war when fired at Fort Sumter, South Carolina. They are still currently on display in front of LSU's Military Science building.

St. Louis interlude

Immediately following his departure from Louisiana, Sherman traveled to Washington, D.C., possibly in the hope of securing a position in the army, and met with Abraham Lincoln in the White House during inauguration week. Sherman expressed concern about the North's poor state of preparedness but found Lincoln unresponsive.

Frank Blair

Thereafter, Sherman became president of the St. Louis Railroad, a streetcar company, a position he would hold for only a few months. Thus, he was living in border-state Missouri as the secession crisis came to a climax. While trying to hold himself aloof from controversy, he observed firsthand the efforts of Congressman Frank Blair, who later served under Sherman, to hold Missouri in the Union. In early April, he declined an offer from the Lincoln administration to take a position in the War Department that might have resulting in his becoming Assistant Secretary of War. After the bombardment of Fort Sumter, Sherman hesitated about committing to military service and ridiculed Lincoln's call for 75,000 three-month volunteers to quell secession, reportedly saying: "Why, you might as well attempt to put out the flames of a burning house with a squirt-gun." However, in May, he offered himself for service in the regular army, and his brother (Senator John Sherman) and other connections maneuvered to get him a commission in the regular army. On June 3, he wrote that "I still think it is to be a long war – very long – much longer than any Politician thinks." He received a telegram summoning him to Washington on June 7.

Civil War

First commissions and Bull Run

Sherman was first commissioned as a colonel in the 13th U.S. Infantry regiment, effective May 14, 1861. This was a new regiment yet to be raised, and Sherman's first command was actually of a brigade of three-month volunteers. With that command, he was one of the few Union officers to distinguish himself at the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861, where he was grazed by bullets in the knee and shoulder. The disastrous Union defeat led Sherman to question his own judgment as an officer and the capacities of his volunteer troops. President Lincoln, however, was impressed by Sherman while visiting the troops on July 23 and promoted him to brigadier general of volunteers (effective May 17, 1861, with seniority in rank to Ulysses S. Grant, his future commander). He was assigned to serve under Robert Anderson in the Department of the Cumberland in Louisville, Kentucky, and in October succeeded Anderson in command of the department. Sherman considered his new assignment to violate a promise from Lincoln that he would not be given such a prominent position.

Robert Anderson

Breakdown and Shiloh

Having succeeded Anderson at Louisville, Sherman now had principal military responsibility for a border state (Kentucky) in which Confederate troops held Columbus and Bowling Green and were present near the Cumberland Gap. He became exceedingly pessimistic about the outlook for his command, and he complained frequently to Washington, D.C., about shortages and provided exaggerated estimates of the strength of the rebel forces. Very critical press reports appeared about him after an October visit to Louisville by the then Secretary of War, Simon Cameron, and in early November Sherman insisted that he be relieved. He was promptly replaced by Don Carlos Buell and transferred to St. Louis, Missouri. In December, however, he was put on leave by Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, commander of the Department of the Missouri, who considered him unfit for duty. Sherman went to Lancaster, Ohio, to recuperate. Some consider that, in Kentucky and Missouri, Sherman was in the midst of what today would be described as a nervous breakdown. While he was at home, his wife, Ellen, wrote to his brother Senator John Sherman seeking advice and complaining of "that melancholy insanity to which your family is subject." Sherman himself later wrote that the concerns of command “broke me down," and he admitted contemplating "suicide." His problems were further compounded when the Cincinnati Commercial described him as "insane."

Don Carlos Buel

Henry Halleck

By mid-December, however, Sherman was sufficiently recovered to return to service under Halleck in the Department of the Missouri (in March, Halleck's command was redesignated the Department of the Mississippi and enlarged to unify command in the West). Sherman's initial assignments were rear-echelon commands, first of an instructional barracks near St. Louis and then command of the District of Cairo. Operating from Paducah, Kentucky, he provided logistical support for the operations of Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant to capture Fort Donelson. Grant, the previous commander of the District of Cairo, had recently won a major victory at Fort Henry and been given command of the ill-defined District of West Tennessee. Although Sherman was technically the senior officer at this time, he wrote to Grant, "I feel anxious about you as I know the great facilities [the Confederates] have of concentration by means of the River and R Road, but [I] have faith in you — Command me in any way."

Ulysses S. Grant

After Grant captured Fort Donelson, Sherman got his wish of serving under Grant when he was assigned on March 1, 1862, to the Army of West Tennessee as commander of the 5th Division. His first major test under Grant was at the Battle of Shiloh. The massive Confederate attack on the morning of April 6, 1862, took most of the senior Union commanders by surprise. Sherman in particular had dismissed the intelligence reports that he had received from militia officers, refusing to believe that Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston would leave his base at Corinth. He took no precautions beyond strengthening his picket lines, refusing to entrench, build abatis, or push out reconnaissance patrols. At Shiloh, he may have wished to avoid appearing overly alarmed in order to escape the kind of criticism he had received in Kentucky. He had written to his wife that, if he took more precautions, "they'd call me crazy again".

Despite being caught unprepared by the attack, Sherman rallied his division and conducted an orderly, fighting retreat that helped avert a disastrous Union rout. Finding Grant at the end of the day sitting under an oak tree in the darkness smoking a cigar, he experienced, in his own words "some wise and sudden instinct not to mention retreat". Instead, in what would become one of the most famous conversations of the war, Sherman said simply: "Well, Grant, we've had the devil's own day, haven't we?" After a puff of his cigar, Grant replied calmly: "Yes. Lick 'em tomorrow, though." Sherman would prove instrumental to the successful Union counterattack of April 7, 1862. At Shiloh, Sherman was wounded twice—in the hand and shoulder—and had three horses shot out from under him. His performance was praised by Grant and Halleck and after the battle, he was promoted to major general of volunteers, effective May 1, 1862.

"Lick 'em tomorrow"

Beginning in late April, a Union force of 100,000 moved slowly against Corinth, under Halleck's command with Grant relegated to a role he found unsatisfactory as second-in-command to Halleck; Sherman commanded the division on the extreme right of the Union's right wing (under George H. Thomas). Shortly after the Union forces occupied Corinth on May 30, Sherman persuaded Grant not to leave his command, despite the serious difficulties he was having with his commander, General Halleck. Sherman offered Grant an example from his own life, "Before the battle of Shiloh, I was cast down by a mere newspaper assertion of 'crazy', but that single battle gave me new life, and I'm now in high feather." He told Grant that, if he remained in the army, "some happy accident might restore you to favor and your true place." In July, Grant's situation improved when Halleck left for the East to become general-in-chief, and Sherman became the military governor of occupied Memphis.

Vicksburg and Chattanooga

The careers of both officers ascended considerably after that time. In Sherman's case, this was in part because he developed close personal ties to Grant during the two years they served together in the West. However, at one point during the long and complicated Vicksburg campaign, one newspaper complained that the "army was being ruined in mud-turtle expeditions, under the leadership of a drunkard [Grant], whose confidential adviser [Sherman] was a lunatic."

John A. McClernand

Sherman's own military record in 1862–63 was mixed. In December 1862, forces under his command suffered a severe repulse at the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou, just north of Vicksburg, Mississippi. Soon after, his XV Corps was ordered to join Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand in his successful assault on Arkansas Post, generally regarded as a politically motivated distraction from the effort to capture Vicksburg. Before the Vicksburg Campaign in the spring of 1863, Sherman expressed serious reservations about the wisdom of Grant's unorthodox strategy,[ but he went on to perform well in that campaign under Grant's supervision. After the surrender of Vicksburg to the Union forces under General Grant on July 4, 1863, Sherman was given the rank of brigadier general in the regular army in addition to his rank as a major general of volunteers. Sherman's family came from Ohio to visit his camp near Vicksburg; their visit resulted in the death of his nine-year-old son, Willie, the Little Sergeant, from typhoid fever.

Patric Clerburne foiled Sherman at the Tunnel Hill fight during Battle of Chattanooga

Thereafter, command in the West was unified under Grant (Military Division of the Mississippi), and Sherman succeeded Grant in command of the Army of the Tennessee. During the Battle of Chattanooga in November, under Grant's overall command, Sherman quickly took his assigned target of Billy Goat Hill at the north end of Missionary Ridge, only to discover that it was not part of the ridge at all, but rather a detached spur separated from the main spine by a rock-strewn ravine. When he attempted to attack the main spine at Tunnel Hill, his troops were repeatedly repulsed by Patrick Cleburne's heavy division, the best unit in Braxton Bragg's army. Sherman's effort was overshadowed by George Henry Thomas's army's successful assault on the center of the Confederate line, a movement originally intended as a diversion. Subsequently, Sherman led a column to relieve Union forces under Ambrose Burnside thought to be in peril at Knoxville and, in February 1864, led an expedition to Meridian, Mississippi, to disrupt Confederate infrastructure.

George H. Thomas

Georgia

Despite this mixed record, Sherman enjoyed Grant's confidence and friendship. When Lincoln called Grant east in the spring of 1864 to take command of all the Union armies, Grant appointed Sherman (by then known to his soldiers as "Uncle Billy") to succeed him as head of the Military Division of the Mississippi, which entailed command of Union troops in the Western Theater of the war. As Grant took overall command of the armies of the United States, Sherman wrote to him outlining his strategy to bring the war to an end concluding that "if you can whip Lee and I can march to the Atlantic I think ol' Uncle Abe will give us twenty days leave to see the young folks."

James B. McPherson

John M. Schofield

Sherman proceeded to invade the state of Georgia with three armies: the 60,000-strong Army of the Cumberland under George Henry Thomas, the 25,000-strong Army of the Tennessee under James B. McPherson, and the 13,000-strong Army of the Ohio under John M. Schofield. He fought a lengthy campaign of maneuver through mountainous terrain against Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston's Army of Tennessee, attempting a direct assault only at the disastrous Battle of Kennesaw Mountain. In July, the cautious Johnston was replaced by the more aggressive John Bell Hood, who played to Sherman's strength by challenging him to direct battles on open ground. Meanwhile, in August, Sherman "learned that I had been commissioned a major-general in the regular army, which was unexpected, and not desired until successful in the capture of Atlanta."

Joseph Johnston

Sherman's Atlanta Campaign concluded successfully on September 2, 1864, with the capture of the city, abandoned by Hood. After ordering all civilians to leave the city, Sherman ordered that all military and government buildings be burned, although many private homes and shops were burned as well. This was to set a precedent for future behavior by his armies. Capturing Atlanta was an accomplishment that made Sherman a household name in the North and helped ensure Lincoln's presidential re-election in November. In the summer of that year, it had appeared likely that Lincoln would be defeated; in August, the Democratic Party nominated as its candidate George B. McClellan, the former Union army commander. Lincoln's defeat might well have meant the victory of the Confederacy, as the Democratic Party platform called for peace negotiations based on the acknowledgment of the Confederacy's independence. Thus the capture of Atlanta, coming when it did, may have been Sherman's greatest contribution to the Union cause.

Abraham Lincoln

John Bell Hood

During September and October, Sherman and Hood played cat-and-mouse in north Georgia (and Alabama) as Hood threatened Sherman's communications to the north. Eventually, Sherman won approval from his superiors for a plan to cut loose from his communications and march south, having advised Grant that he could "make Georgia howl." This created the threat that Hood would move north into Tennessee. Trivializing that threat, Sherman reportedly said that he would "give [Hood] his rations" to go in that direction as "my business is down south." However, Sherman left forces under Maj. Gens. George H. Thomas and John M. Schofield to deal with Hood; their forces eventually smashed Hood's army in the battles of Franklin (November 30) and Nashville (December 15-16). Meanwhile, after the November elections, Sherman began a march with 62,000 men to the port of Savannah, Georgia, living off the land and causing, by his own estimate, more than $100 million in property damage. Sherman called this harsh tactic of material war "hard war", often seen as a species of total war. At the end of this campaign, known as Sherman's March to the Sea, his troops captured Savannah on December 21, 1864. Sherman then dispatched a famous message to Lincoln, offering him the city as a Christmas present.

Sherman's success in Georgia received ample coverage in the Northern press at a time when Grant seemed to be making little progress in his fight against Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. A bill was introduced in Congress to promote Sherman to Grant's rank of lieutenant general, probably with a view towards having him replace Grant as commander of the Union Army. Sherman wrote both to his brother, Senator John Sherman, and to General Grant vehemently repudiating any such promotion. According to a war-time account, it was around this time that Sherman made his memorable declaration of loyalty to Grant:

“It is related that a distinguished civilian, who visited him at Savannah, desirous of ascertaining his real opinion of General Grant, began to speak of him in terms of depreciation. "It won't do; it won't do, Mr. _____," said Sherman, in his quick, nervous way; "General Grant is a great general. I know him well. He stood by me when I was crazy, and I stood by him when he was drunk; and now, sir, we stand by each other always."

While in Savannah, Sherman also suffered the blow of learning from a newspaper that his infant son Charles Celestine had died during the march to the sea; the general had never even seen the child.

Final campaigns in the Carolinas

For the next step, Grant initially ordered Sherman to embark his army on steamers to join the Union forces confronting Lee in Virginia. Instead, Sherman persuaded Grant to allow him to march north through the Carolinas, destroying everything of military value along the way, as he had done in Georgia. He was particularly interested in targeting South Carolina, the first state to secede from the Union, for the effect it would have on Southern morale. His army proceeded north through South Carolina against light resistance from the troops of Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston. Upon hearing that Sherman's men were advancing on corduroy roads through the Salkehatchie swamps at a rate of a dozen miles per day, Johnston "made up his mind that there had been no such army in existence since the days of Julius Caesar."

Sherman's army moves through the Salkehatchie swamps

Sherman captured the state capital of Columbia, South Carolina, on February 17, 1865. Fires began that night and by next morning, most of the central city was destroyed. The burning of Columbia has engendered controversy ever since, with some claiming the fires were accidental, others a deliberate act of vengeance, and still others that the retreating Confederates burned bales of cotton on their way out of town. Local Native American Lumbee guides helped Sherman's army cross the Lumber River through torrential rains and into North Carolina. According to Sherman, the trek across the Lumber River, and through the swamps, pocosins, and creeks of Robeson County "was the damnedest marching I ever saw". Thereafter, his troops did little damage to the civilian infrastructure, as North Carolina, unlike its southern neighbor, which was seen as a hotbed of secession, was regarded by his men to be only a reluctant Confederate state, due to its position as one of the last to join the Confederacy. In late March, Sherman briefly left his forces and traveled to City Point, Virginia, to consult with Grant. Lincoln happened to be at City Point at the same time, allowing the only three-way meeting of Lincoln, Grant, and Sherman during the war.

Sherman, Grant, Lincoln, & Porter meet at City Point

Following Sherman's victory over Johnston's troops at the Battle of Bentonville, Lee's surrender to Grant at Appomattox Court House, and Lincoln's assassination, Sherman met with Johnston at Bennett Place in Durham, North Carolina, to negotiate a Confederate surrender. At the insistence of Johnston and Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Sherman offered generous terms that dealt with both political and military issues. Sherman thought his terms were consistent with the views Lincoln had expressed at City Point, but the general had no authority to offer such terms from General Grant, newly installed President Andrew Johnson, or the Cabinet. The government in Washington, D.C., refused to honor the terms, precipitating a long-lasting feud between Sherman and the Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton. Confusion over this issue lasted until April 26, 1865, when Johnston, ignoring instructions from President Davis, agreed to purely military terms and formally surrendered his army and all the Confederate forces in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida, becoming the largest surrender of the American Civil War. Sherman proceeded with his troops to Washington, D.C., where they marched in the Grand Review of the Armies on May 24, 1865 and were then disbanded. Having become the second most important general in the Union army, he thus had come full circle to the city where he started his war-time service as colonel of a non-existent infantry regiment.

Andrew Johnson

Edwin M. Stanton

Postbellum service

In May 1865, after the major Confederate armies had surrendered, Sherman wrote in a personal letter:

“I confess, without shame, I am sick and tired of fighting—its glory is all moonshine; even success the most brilliant is over dead and mangled bodies, with the anguish and lamentations of distant families, appealing to me for sons, husbands and fathers ... [I]t is only those who have never heard a shot, never heard the shriek and groans of the wounded and lacerated ... that cry aloud for more blood, more vengeance, more desolation.â€

In July 1865, only three months after Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, General W. T. Sherman was put in charge of the Military Division of the Missouri, which included every territory west of the Mississippi. Sherman's main concern as commanding general was to protect the construction and operation of the railroads from attack by hostile Indians. In his campaigns against the Indian tribes, Sherman repeated his Civil War strategy by seeking not only to defeat the enemy's soldiers, but also to destroy the resources that allowed the enemy to sustain its warfare. The policies he implemented included the extensive killing of large numbers of buffalo, which were the primary source of food for the Plains Indians.

Despite his harsh treatment of the warring tribes, Sherman spoke out against the unfair way speculators and government agents treated the natives within the reservations.

Sherman at the Fort Laramie treaty

On July 25, 1866, Congress created the rank of General of the Army for Grant and then promoted Sherman to lieutenant general. When Grant became president in 1869, Sherman was appointed Commanding General of the United States Army. After the death of John A. Rawlins, Sherman also served for one month as interim Secretary of War. His tenure as commanding general was marred by political difficulties, and from 1874 to 1876, he moved his headquarters to St. Louis, Missouri in an attempt to escape from them. One of his significant contributions as head of the Army was the establishment of the Command School (now the Command and General Staff College) at Fort Leavenworth.

Sherman stepped down as commanding general on November 1, 1883, and retired from the army on February 8, 1884. He lived most of the rest of his life in New York City. He was devoted to the theater and to amateur painting and was much in demand as a colorful speaker at dinners and banquets, in which he indulged a fondness for quoting Shakespeare. Sherman was proposed as a Republican candidate for the presidential election of 1884, but declined as emphatically as possible, saying, "If drafted, I will not run; if nominated, I will not accept; if elected, I will not serve." Such a categorical rejection of a candidacy is now referred to as a "Shermanesque statement".

Autobiography & Memoirs

Around 1868, Sherman wrote (or at least began) a “private†recollection for his children about his life before the Civil War — identified now as his unpublished “Autobiography, 1828-1861.†Much of the material in it would eventually be incorporated in revised form in his memoirs.

In 1875, ten years after the end of the Civil War, Sherman became one of the first Civil War generals to publish a memoir. The memoirs were controversial, and sparked complaints from many quarters. Grant (serving as President when Sherman’s memoirs first appeared) later remarked that others had told him that Sherman treated Grant unfairly but “when I finished the book, I found I approved every word; that . . . it was a true book, an honorable book, creditable to Sherman, just to his companions — to myself particularly so — just such a book as I expected Sherman would write.â€

Death

Sherman died in New York City on February 14, 1891. On February 19, there was a funeral service held at his home there, followed by a military procession. Sherman's body was then transported to St. Louis, where another service was conducted on February 21, 1891 at a local Catholic church. His son, Thomas Ewing Sherman, a Jesuit priest, presided over his father's funeral mass. General Joseph E. Johnston, the Confederate officer who had commanded the resistance to Sherman's troops in Georgia and the Carolinas, served as a pallbearer in New York City. It was a bitterly cold day and a friend of Johnston, fearing that the general might become ill, asked him to put on his hat. Johnston famously replied: "If I were in [Sherman's] place, and he were standing in mine, he would not put on his hat." Johnston did catch a serious cold and died one month later of pneumonia.

Sherman is buried in Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis. Major memorials to Sherman include the gilded bronze equestrian statue by Augustus Saint-Gaudens at the main entrance to Central Park in New York City and the major monument by Carl Rohl-Smith near President's Park in Washington, D.C.

Try the BEST MySpace Editor and MySpace Backgrounds at MySpace Toolbox !