Far above the Arctic circle, at a latitude of 79 degrees North, is the

Norwegian coal-mine of Longyearbyen. It was here, in one of the world's most

inhospitable continuously inhabited communities, that Didrik Eide used to earn

his living. His job as an explosives engineer took him deep below the frozen

tundra. The pattern of his working life - drill holes in the coal-face, set the

charges, run for cover - incorporated mechanical rhythms, loud noises and

extreme danger.

Small wonder then, that when he started making music of his own - using the same laptop on which he worked out the correct explosives ratios - the

contours of those sounds were soft and almost pastoral. It wasn't the noise of

the explosions that haunted him, but the claustrophobic silence of the

subterranean chambers in which he made those life or death calculations. When

he'd emerge from the top of the mineshaft at the end of an eighteen hour shift,

his ears would pop in response to the change in air-pressure, and his eyes

would smart at the unaccustomed brightness.

In Longyearbyen, the sun rises and sets for just six weeks in the spring and six weeks in the autumn. In the summer months, the closest it gets to night is a few hours of ellipse, when the sun's rays still flood the

landscape from just below the horizon. In the winter, the combination of The

Northern Lights and moonlight reflecting from glacial snowscapes ensures that

it's always bright enough to read a newspaper outside (should you have a

sufficiently hardy constitution to cope with the bone-cracking cold). When Eide

left the mine - after an accident in a maintenance tunnel claimed the life of

several schoolfriends - he found himself voyaging around the world, first as a

crew-hand on a whaling ship, and subsequently as a bodyguard for an

international salesman of controversial metal-testing equipment.

The further he travelled from Longyearbyen, the more clearly Didrik

remembered the sensation of emerging from that mineshaft. He finally ended up

in North Wales, with a vague idea of using his explosives experience in the

slate industry, but a chance visit to a second-hand record shop found him

rekindling the love for pure sound which had all but died out in the years

since he'd left home. Hearing music by Kraftwerk and The Aphex Twin inspired

him to return to that same battered laptop. And he began to combine the gentle,

reassuring textures of the recordings he'd made as a younger man, with colder,

crisper, more machine-like sounds, which somehow expressed the nostalgia he'd

started to feel for the life he'd left behind him.

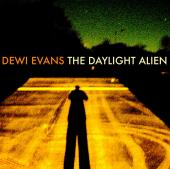

When Didrik Eide played his songs to other people for the first time,

they told him they liked the sense of yearning it seemed to contain, for the

kind of communal pleasures - often celebrated in dance music - which his

solitary (though dramatic) odyssey had generally denied him. So he chose to

release this music under the name "The Daylight Alien", as it seemed to reflect

both the isolation he felt as a stranger, struggling to establish himself anew

in a close-knit community, and that magical cloak of strangeness had once

seemed to drape across his shoulders, as he came up out of the dark into that

endless, eerie Arctic light.

Ben Thompson